Tomorrow is The United States’ 249th birthday! I hope everyone’s day is filled with a “reflective patriotism” (Thank you for the word, Alexis De Tocqueville).

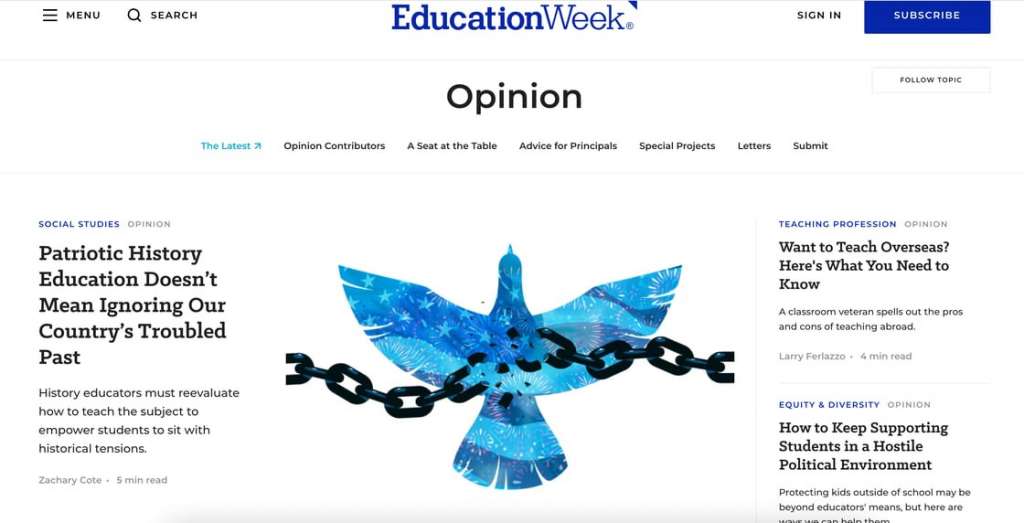

Speaking of reflective patriotism, it’s been on my mind a lot lately. In fact, last week, Education Week published my piece “Patriotic History Education Doesn’t Mean Ignoring Our Country’s Troubled Past.” As an American, I love my country. As a scholar, I know she is far from perfect. In the piece, I argue that historical thinking enables us to have a love of country that doesn’t demand turning a blind eye to the injustices in our country’s past. Great Americans such as Frederick Douglass and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. modeled this well. Here is an excerpt:

“I love America. I love it for what it is. But I don’t always love what it does. My love for my country is not based on

circumstance or performance. It is an unconditional love that does not ignore its flaws.

My training in history enables my practice of this love. I’ve learned tools of investigation and interpretation that allow

me to wrestle with moral tensions and proactively try to better understand the United States throughout its complex

past…

Schools must approach history differently. When we history educators teach the subject as a discipline defined by

investigation and interpretation, students can better confront the crippling nature of singular narratives like American

greatness or American oppression. This reorientation can cultivate a rising generation of people equipped with civic

dispositions that are necessary to sustain a democracy…

To cultivate a reflective patriotism in future generations, we must commit to teaching history as a set of skills rather

than a list of dates and events. History is a discipline (the study of the past), not a content (the past). Many of our K-12

history standards, textbooks, and courses narrowly focus on that content at the expense of teaching students the

dispositions necessary for the discipline. When we only focus on the content, we often fight over whose history is

better or more accurate, which only furthers our national divide. A focus on content makes us choose between 1619

and 1776; a disciplinary approach empowers us to recognize the historical significance of both.”

In short, being empowered with historical thinking does in fact give us the tools to contribute to a flourishing democracy. Please head over the Education Week to read the whole piece.

Happy Independence Day!

Zachary Cote

Executive Director

Partner with Us!