Richard Feynman, the famed American theoretical physicist who notably worked alongside J. Robert Oppenheimer during the building of the first atomic bomb, once said, “If you can’t explain something in simple terms, then you don’t understand it yourself.” This quote by Feynman highlights the not-so-obvious fact that in order to truly master a concept, idea, or theory, one must be able to explain it and teach it to others.

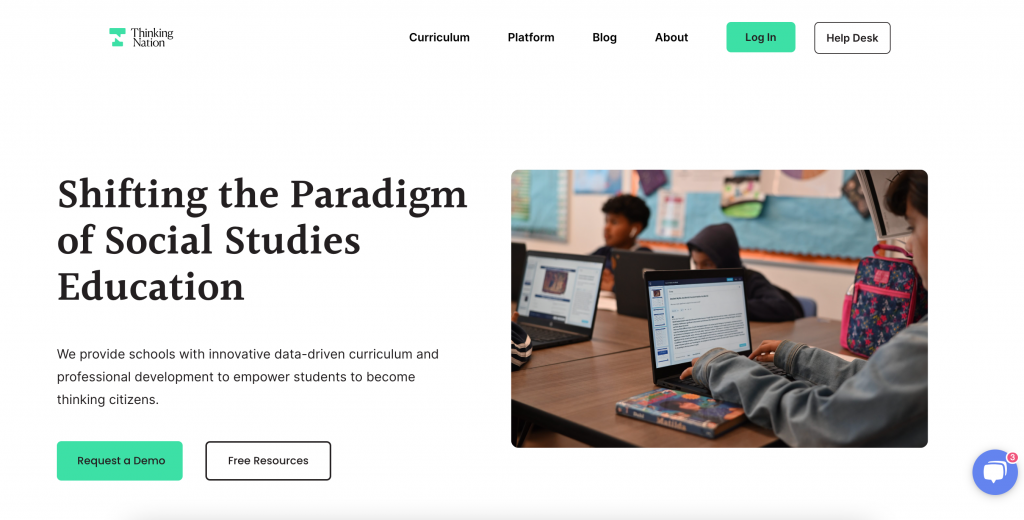

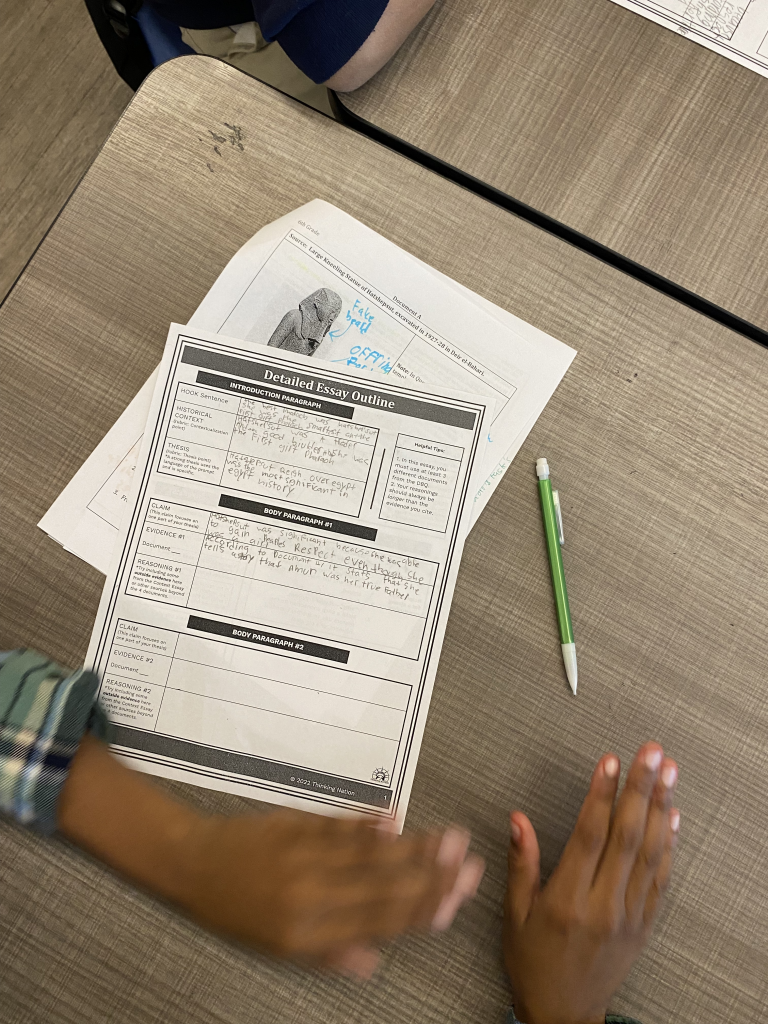

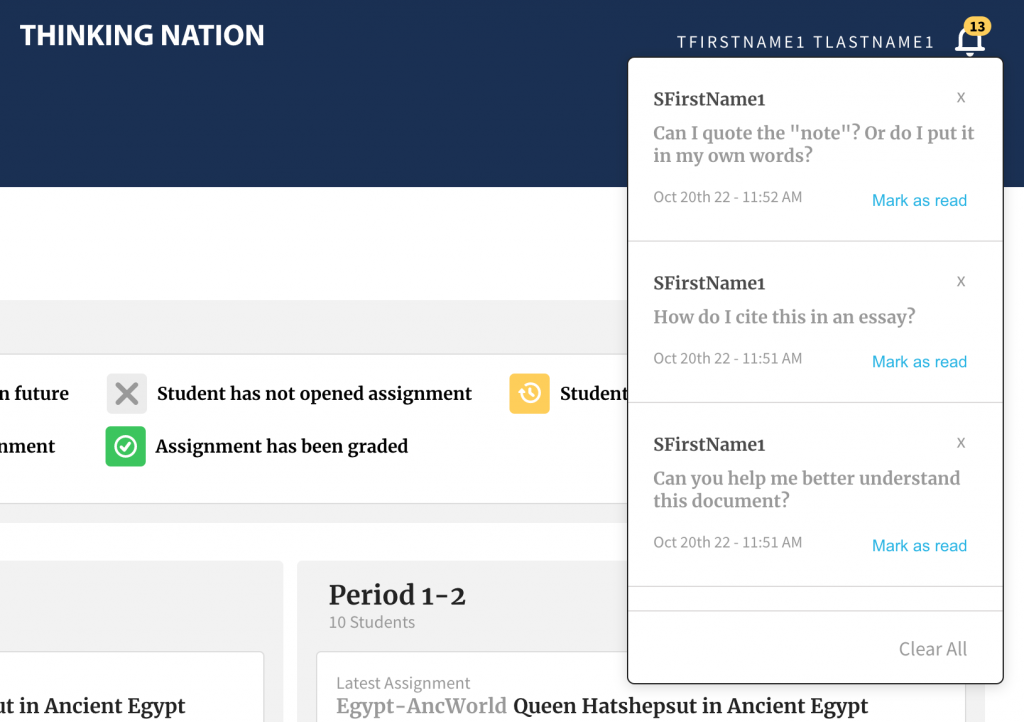

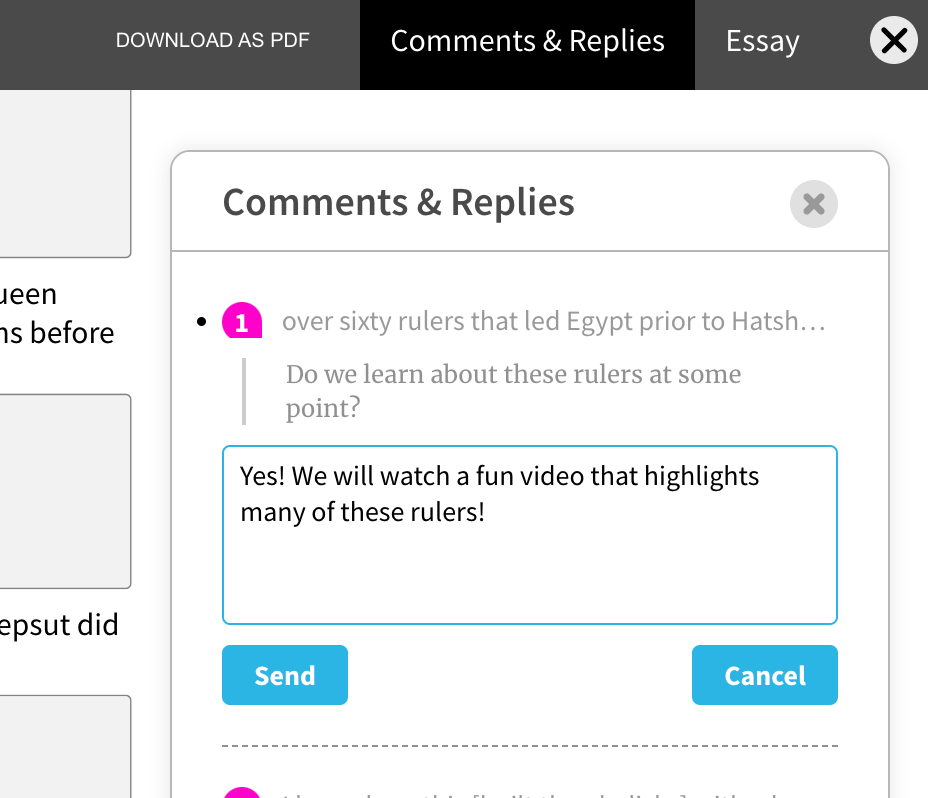

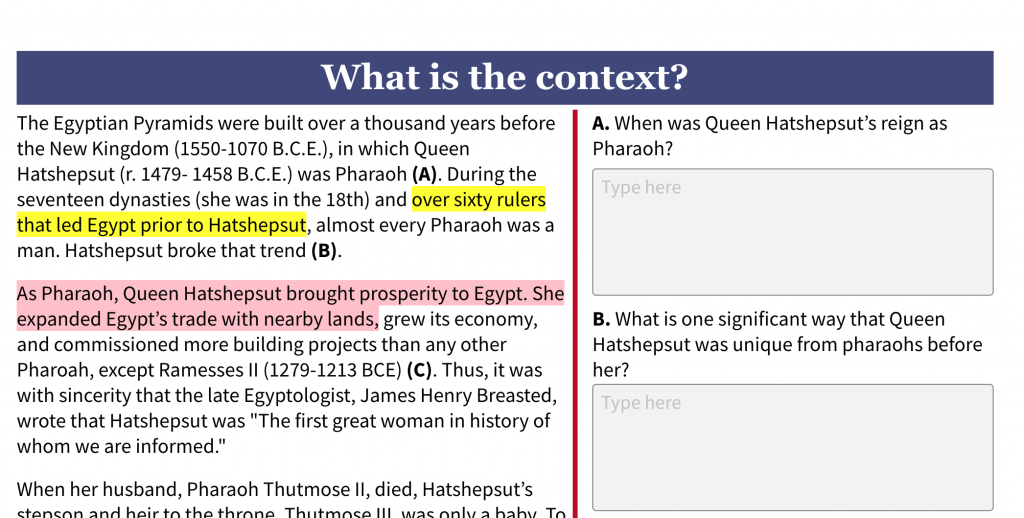

During the past couple of months at Thinking Nation, we have been working on developing graphic organizers that can support students in understanding how to apply and interpret historical thinking skills. Specifically, we have created graphic organizers that have focused on the historical thinking skills related to continuity and change over time, evaluating evidence, evaluating perspectives, evaluating arguments, and quantitative analysis. These historical thinking skills, while complex, are essential in helping students think critically and deeply about historical events.

The process of creating these graphic organizers has been a team effort by Thinking Nation’s curriculum staff. On one document, for instance, we made over dozens of edits trying to simplify the language, visuals, instructions, and graphics for both middle and high school students. Just when we thought we had finally captured the essence of the historical thinking skill in the graphic organizer, one more comment or a bit more feedback would send us back into another review cycle. The refinement process has been long, but has produced solid work that takes multifaceted historical thinking skills and shows students how to apply them.

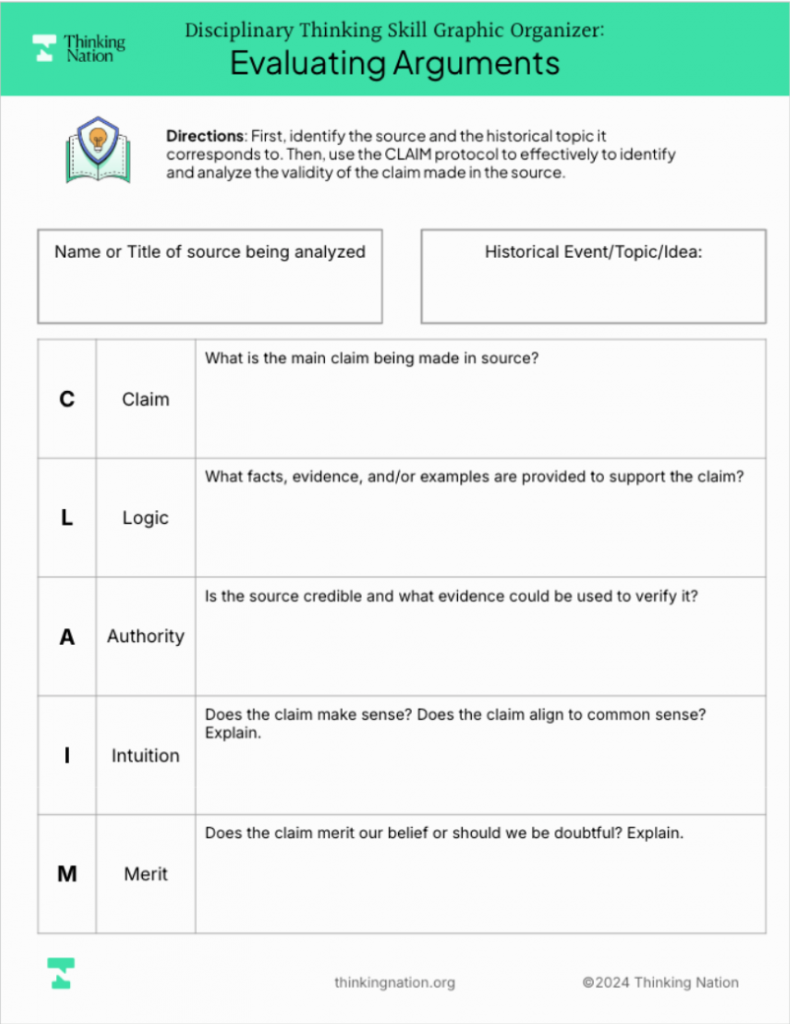

For example, in primary sources and secondary sources students often encounter different types of claims made by historical figures. Not all claims are equal, and history students need a systematic method for evaluating these claims. To help students, we developed a simple acronym titled “CLAIM.” CLAIM stands for: Claim, Logic, Authority, Intuition, and Merit. Each of the letters in the acronym is aligned to a specific element for evaluating claims, and has scaffolded questions that help students methodically evaluate the claim.

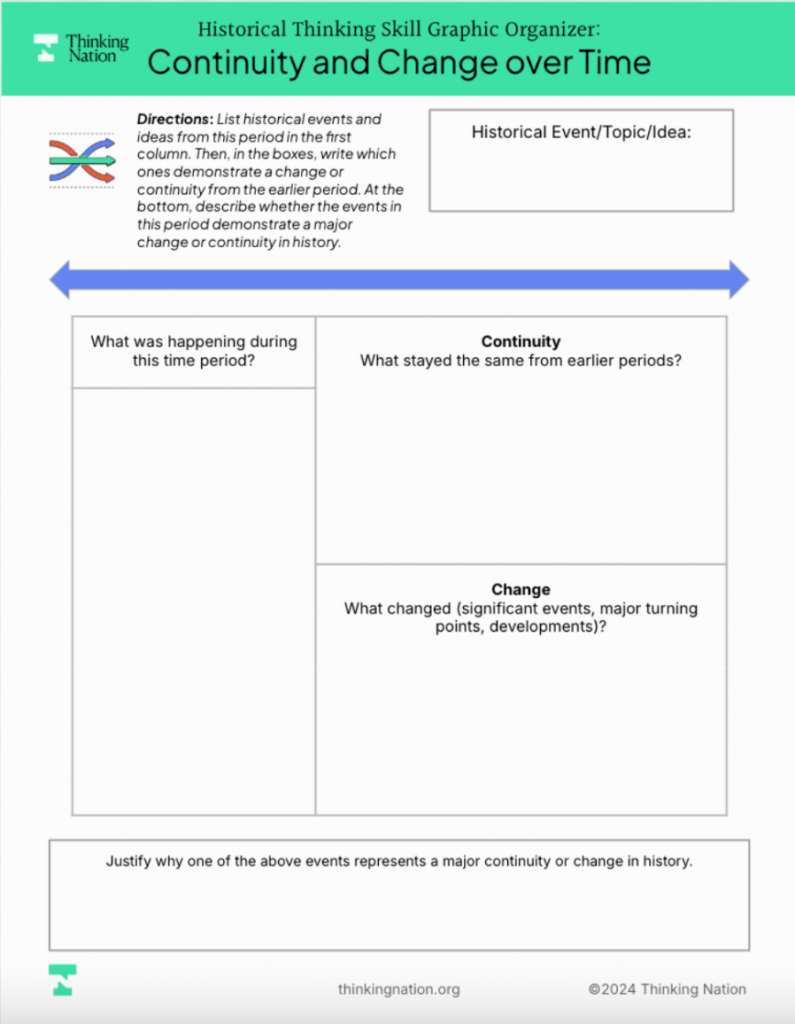

Another example of how we took complex concepts and created resources for students to use can be seen through the continuity and change graphic organizer. In history, there are hundreds of events that have precipitated great changes for people and society. During the era of Reconstruction, for instance, social life for many African Americans changed throughout the country, yet economic opportunities remained out of reach for many newly emancipated people, who, out of necessity, turned to sharecropping. The advanced graphic organizer developed by our Thinking Nation team allows students to unpack historical events – like the Era of Reconstruction – and analyze the juxtaposition of what changed and what continued on for a particular group in society. Additionally, students are asked to justify why one of the cited examples in the graphic organizer represents a major continuity or change in history.

Throughout his life, Richard Feyman wrote and lectured extensively about concepts related to quantum mechanics and physics. His books have sold widely in various languages throughout the world because of their broad readability and for the ways Feynman made complex ideas accessible to laymen. The ability to explain the complex to others and to simplify multifaceted concepts takes skill, time, and effort. The work we did here at Thinking Nation over the past month will help explain complex concepts in simple terms to students, and will help teachers teach and reinforce those skills over the course of the school year. As a team, we are proud of the work we did and are convinced that it will help students become better historical thinkers!

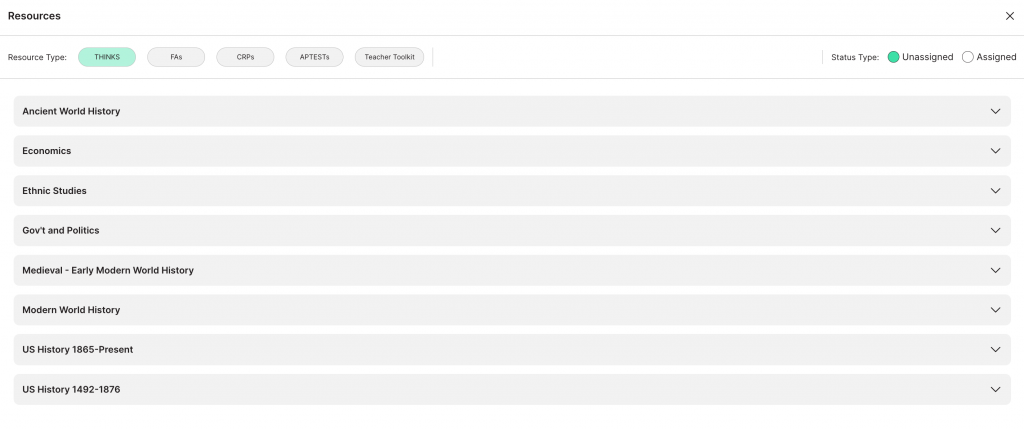

THINKING NATION TEACHERS! Head to the Teacher Tool Kit when logged in to download all of the new graphic organizers!