At the end of last school year, many of the teachers we work with had a common reflection. It went something like this: “While I appreciate seeing the robust data from the Curated Research Papers, I don’t have enough time to do these often. I do really enjoy the formative assessments on historical thinking, though. The ability to assess a student on a particular thinking skill in a short (less than 30 minute) time span is incredibly helpful for gauging student growth. Can you make more?”

Yes, yes, we can.

Over the summer, we gave ourselves the goal of having 4 formative assessments for all 80+ of our current units. This meant that we would have to more than double the amount of formative assessments we offered on our platform. So we did! As a rule of thumb, I often recommend that teachers implement a formative assessment on disciplinary thinking every other week in their classes. With over 40 available for teachers in each of our course offerings, this is now an easy feat to accomplish.

Why formative assessments?

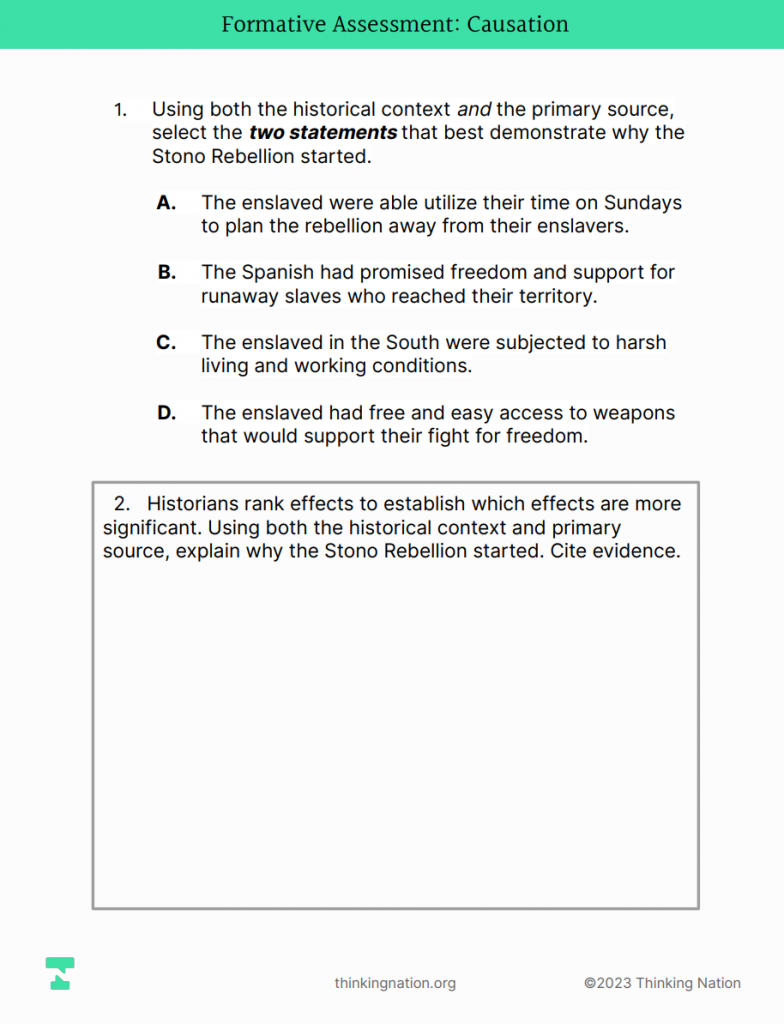

We’ve identified 8 different skills to assess in our formative assessments (We recently added Quantitative Analysis!). Essentially, these assessments are stimulus-based, consist of one “Weighted Multiple Choice” (WMC) question and one “justification” short answer question. Here is a sample for the skill “causation.” Our goal with our formative assessments is to help whole departments shift their own paradigm for how they measure student success.

Usually, formative assessments in social studies classrooms consist of memory-based assessments to ensure that students have retained the information taught. Essentially, success is measured by a student’s ability to retell us what we told them earlier. However, this is not historical thinking.

Our formative assessments on historical thinking allow for teachers to assess how the students approach the information they engage with, rather than simply their ability to remember it. For instance, in the sample linked above, students are presented with historical context and a primary source. The WMC question asks them to use those sources in order to select the two strongest statements that describe why an event happened. Then, the short answer component asks them to defend one of those statements as the stronger cause for the event, citing evidence in their justification.

This simple task on causation emphasizes two key components of the historical thinking skill of causation. First, nothing is monocausal: “select two.” Second, historians make evidence-based arguments about the past. This second part is critical if we want to empower our students with the agency to enter into nuanced conversation, whether about the past or our present.

Vertical Alignment through Historical Thinking

Another critical component of these formative assessments is that whole departments can norm around them. In fact, the idea of building collaboration without losing teacher autonomy was the focus of my California Council for Social Studies session back in February 2023. Social Studies departments have been siloed by content for too long and our formative assessments give teachers a common language for success regardless of the content of their classroom. If teachers of different subjects each gave a formative assessment on causation, they could then come together and have meaningful and productive conversations around student success, as well as create aligned goals across the department. Common assessments transform history departments.

We cannot shift the paradigm of social studies education without a common language for success. Formative assessments on historical thinking can help get us there. That’s why we listened to teacher feedback and more than doubled our offerings of this particular assessment tool.