When I lead professional developments for teachers, I don’t shy away from the difficulty of teaching students to think historically. It’s rigorous, time consuming, and at times, frustrating. When we ask students to think historically, merely restating historical facts is no longer sufficient. Students need to interrogate past documents and perspectives in order to make evidence-based statements and draw conclusions for themselves. It’s hard. Still, I remind teachers that just because teaching historical thinking is difficult, does not mean it can’t be simple. Sometimes, simple is best.

At Thinking Nation, we are not trying to develop the next best educational buzzword. We aren’t trying to fill our curriculum with abundant strategies, games, interactives, or whatever the latest trend in education has become. Rather, we are looking to cultivate thinking citizens with targeted approaches to teaching historical thinking. What does this look like?

Well, to start, we want to introduce students to the practice of reading, interpreting, and synthesizing primary sources. These rich documents of the past are filled with so much insight to whatever moment in time they hail from that it is key that we don’t simply read them to remember what they said. Instead, we need to read them, ask questions of them, interrogate their authors, seek to understand their premise and historical context, and connect them to a larger vision of the past. Reading historical documents is not merely reading for knowledge. It is reading for understanding.

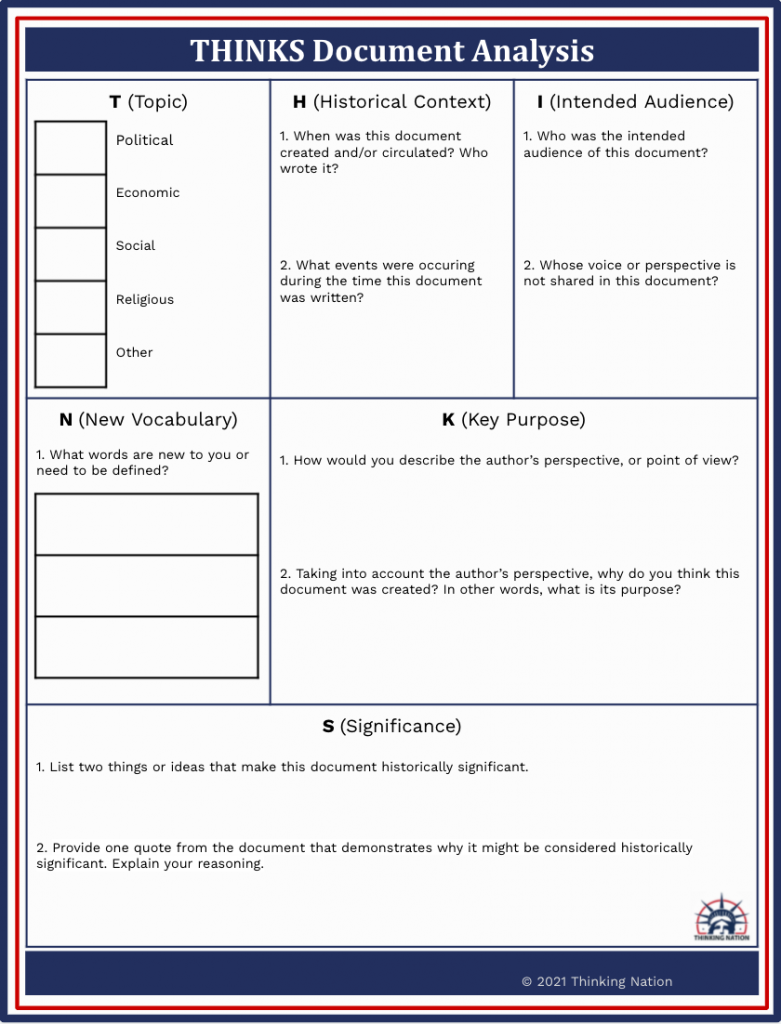

Our simple yet effective approach to teaching students this skill comes in the form of a graphic organizer. When students read a primary (and sometimes secondary) source within our materials, they use our “THINKS” graphic organizer to guide their own reading of the document. (Download a sample!) THINKS is a simple acronym that helps students think more deeply about the text.

Last week, I had the privilege of conducting a guest lesson at a large LA high school. We read a 7 sentence excerpt of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations where he highlights the benefits of his theory of Division of Labor. I began the class with a simple breakdown of the term using Frayer’s Model, and then dedicated the next 70 minutes to those 7 sentences. All the students had in hand was the source and their THINKS graphic organizer.

TIME FLEW. We interrogated the text using the prompting questions from the organizer. We dug deep in order to understand the context, purpose, and significance of Smith’s claim. We asked questions to challenge his claim. We identified new vocabulary. We did so much.

Of course, the process must be refined more for students so they can internalize this approach to reading the past, but it was an incredibly successful start. The students were engaged and boring Adam Smith came alive. The historical thinking we engaged in was rigorous and difficult, but the process was simple. Students had a simple tool to help guide them on their road to historical thinking.