On September 19th, our friends at the American Historical Association published a deeply needed report on the state of American History education in the United States. Having had the opportunity to work alongside the AHA’s Director of Teaching and Learning, Brendan Gillis, as well as speaking with two of the researchers on the report, Nicholas Kryczka and Scot McFarlane, as they finalized the project, I want to affirm just how much work went into this report. It is a prime example of what historians can bring to better understand the educational landscape in this country.

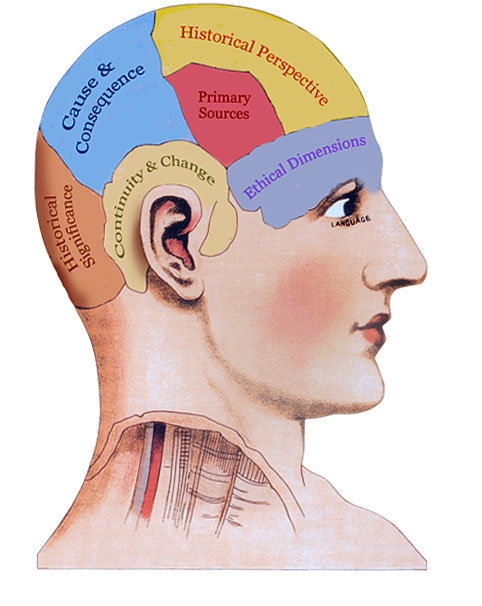

Before I get into the main part of my own reflections on the report, I also want to shout out Scot McFarlane’s new initiative, the Oxbow History Company. The vision behind Oxbow, to take the tools of the historian and apply it to a variety of contexts, is brilliant.

Back to the report. Both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times published articles in response to the publication of the American Historical Association report: American Lesson Plan: Teaching US History in Secondary Schools. I appreciate that the report was referenced by these national news outlets, and, at least in the case of the New York Times, represented well. As part of my own reflective exercise, I responded to them both. I linked the original articles before my responses, and I encourage you to read them. I also hope that these responses are helpful as we think about how we can use this report to shift the paradigm of history education.

Response to the New York Times

As Dana Goldstein summarized, the American Historical Association report on history education is a needed anchor. Without this data, we might believe the polarizing narratives that teachers use their classrooms to indoctrinate students on their particular view of American history. These narratives come from both left and right.

The AHA report paints a better picture. It is a testament to the power of research and evidence. It reminds us that history teachers are professionals. Most history teachers take their job seriously to present “multiple sides of every story.” They root their classrooms in evidence.

In the face of narratives that opine otherwise, let’s remember John Adams’ comment during the Boston Massacre trial, “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.”

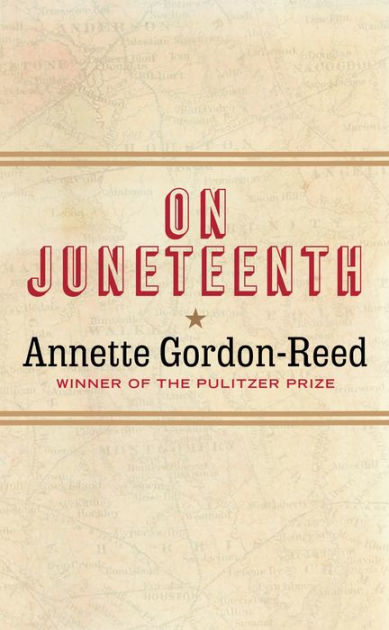

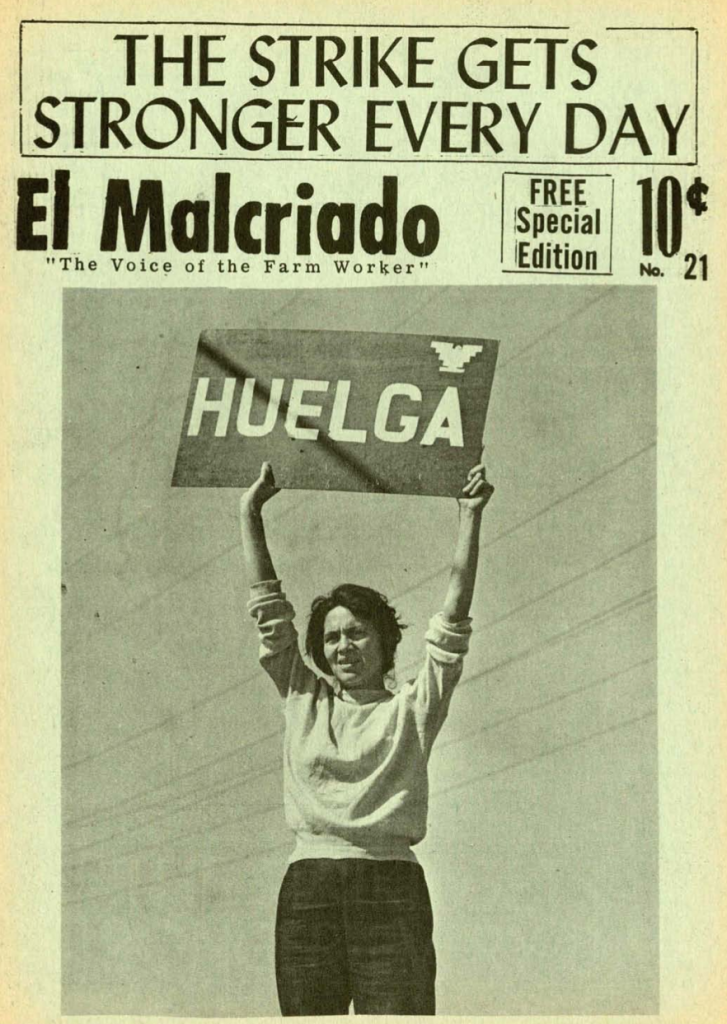

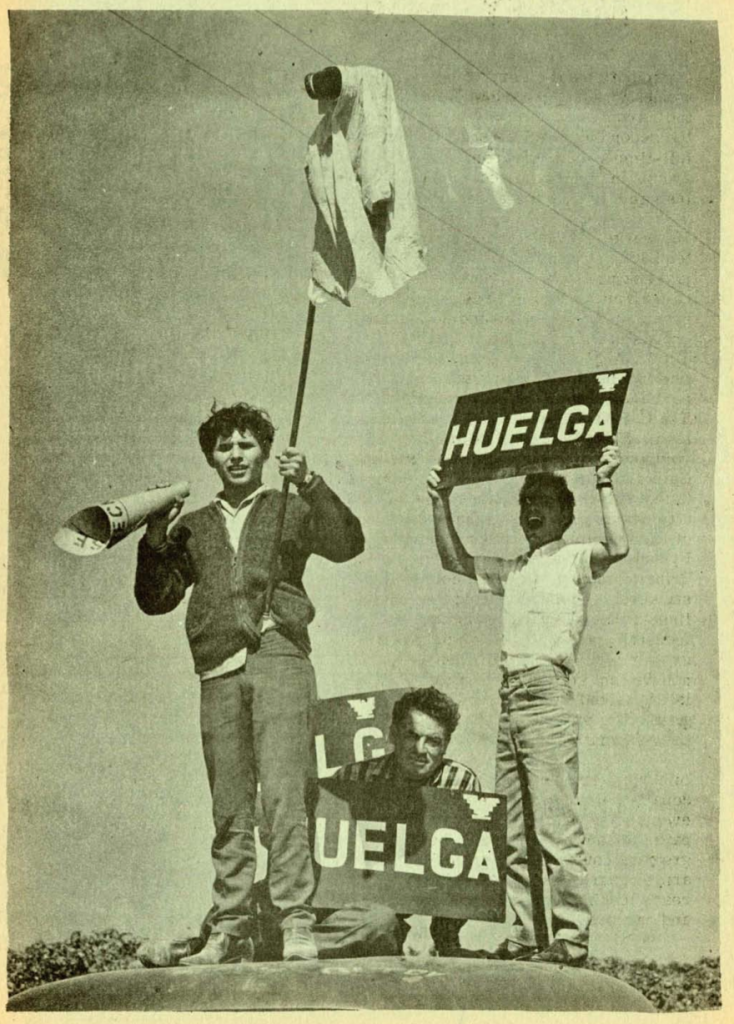

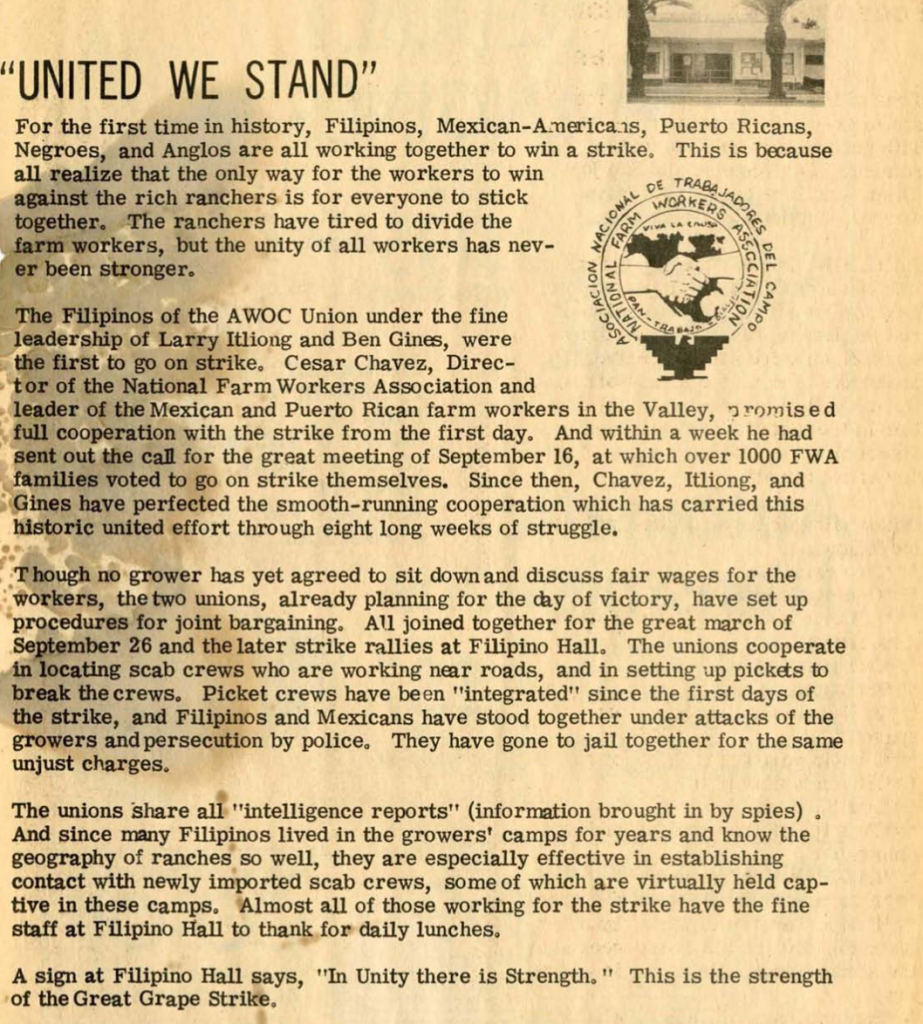

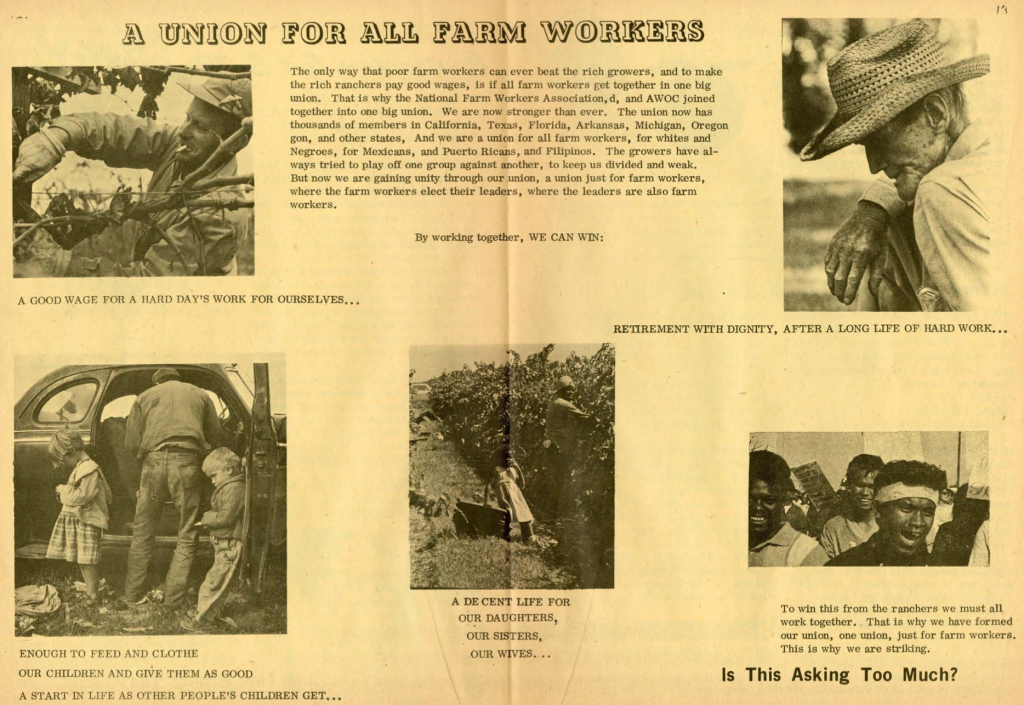

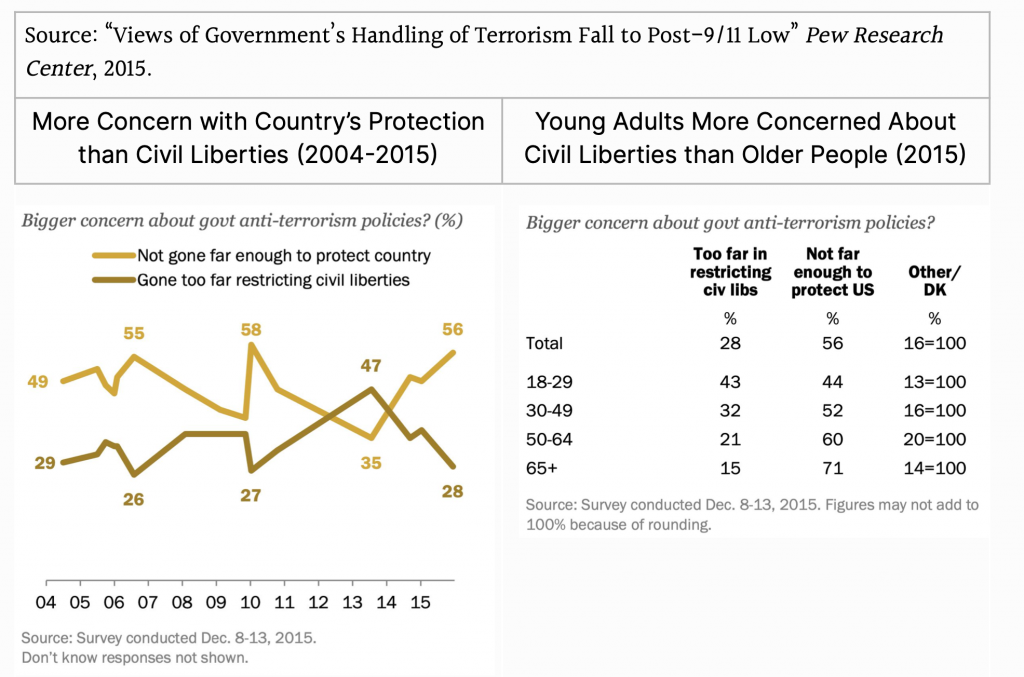

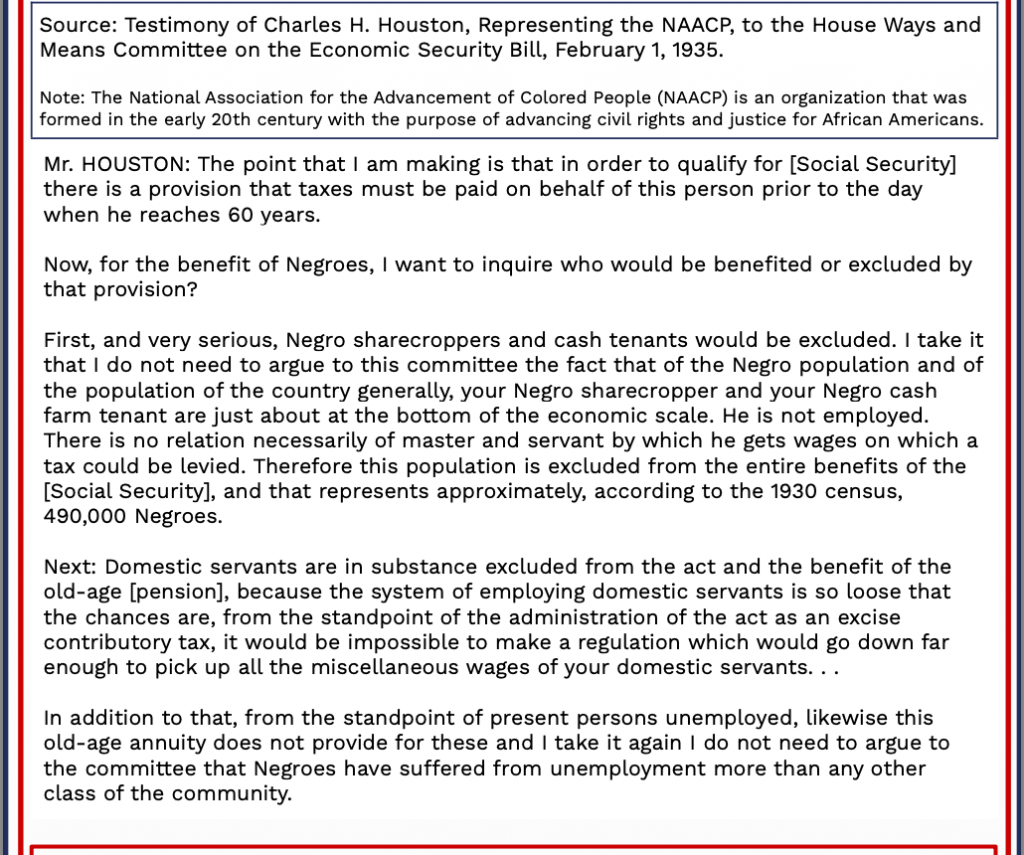

While the article acknowledges how teachers utilize primary sources, like the one above, I want to underscore how important this is. Giving students the opportunity to analyze primary sources empowers them to think critically, gain empathy for multiple perspectives, and effectively evaluate evidence. Let’s better support teachers in this work. These skills can strengthen both public education and our pluralistic democracy.

Response to the Los Angeles Times

LZ Granderson’s article highlighting the American Historical Association’s American History report draws needed attention to the state of history education. After reading the report, however, Granderson’s thesis seems incongruent with its findings. The report is not a reckoning of how history is taught, but an outline of the good work being done in history classrooms.

Of course, some of Granderson’s concerns over our nation’s collective knowledge of the past are warranted and need to be addressed. But, to say a report on education in American history classrooms “is not going to be pretty” severely misrepresents the AHA’s findings. The AHA notes that it “did not find indoctrination, politicization, or classroom malpractice.” History teachers are doing good work.

The evidence-based history that many teachers prioritize is a model for how to engage with the past. The AHA report embodies hope for American history education. Granderson’s problem may be there, but it’s not in our classrooms.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13666403/ED631C7C_CD1F_4A54_BCAD_56F2886B5172.jpeg)