When visiting one of our partner schools this week, I was able to watch students engage in the writing process using Thinking Nation DBQs centered on historical thinking. At this particular Los Angeles middle school, the 6th and 8th grade classrooms sit directly across the hallway from each other, allowing me to bounce between the two classes while on campus.

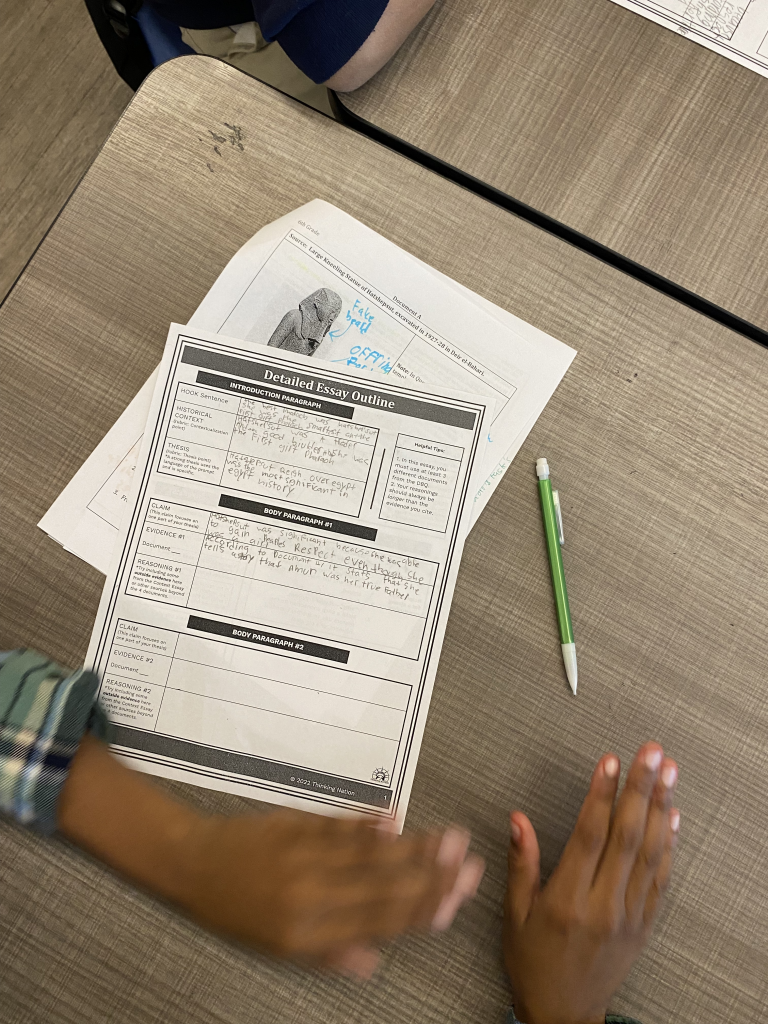

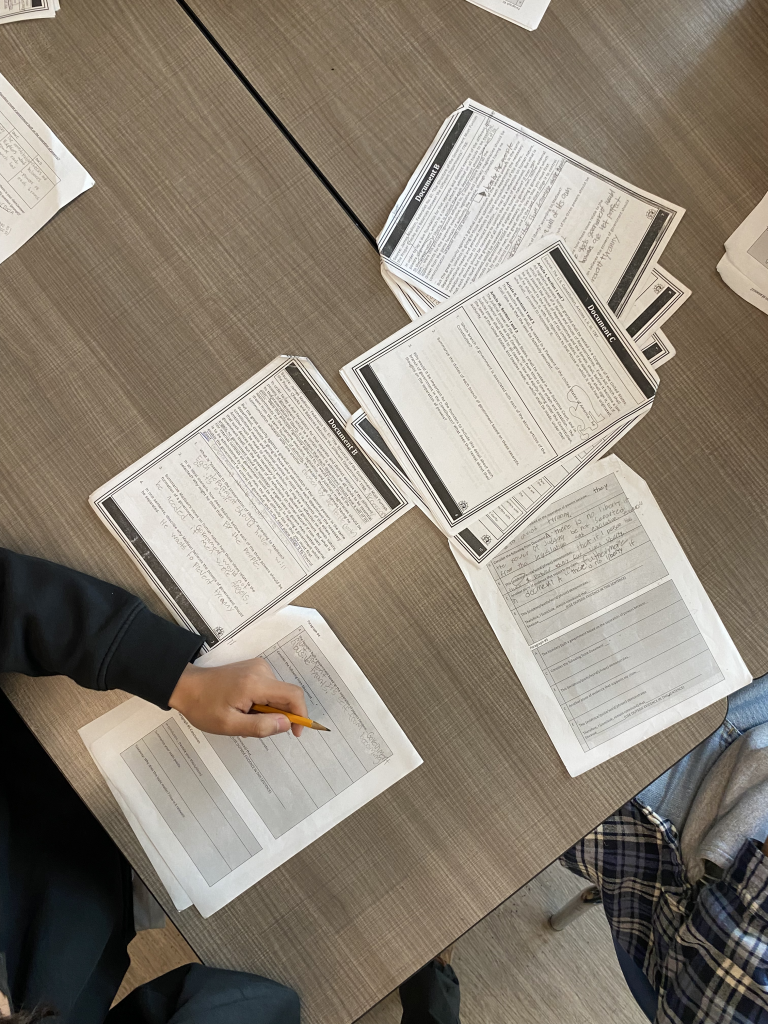

In the 6th grade classroom, students were beginning the outlining process for writing an essay to answer the question: In what ways was Queen Hatshepsut’s reign as Pharaoh of Egypt historically significant? In the 8th grade classroom, students were about half way through outlining their essays to answer the question: Why did the founders create a government built on the separation of powers?

Both groups of students were thinking critically about primary source materials in order to answer those questions. For the 15-20 minutes that I was able to hang out in each classroom, I saw all types of analysis as students engaged with the material. 6th grade students were looking at pictures of statues of Hatshepsut and noting how she portrayed herself as a deity in order to give herself legitimacy as a female pharaoh in a largely male-dominated society. They drew attention to her building projects like her massive obelisks or her mortuary temple, Deir el-Bahari. Students were constructing a thesis statement that highlighted how accomplishments like this made her historically significant.

In the 8th grade classroom, most students were interrogating James Madison’s meaning for the behind “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition” and thinking of clever ways to word their paragraphs in order to explain how the founders wanted to build a government that recognized the inherent selfishness that Madison saw in human nature. Their conversations straddled the line between history and philosophy and it was inspiring to listen in and even engage with some of their thoughts.

In both cases, students were not merely passively receiving a historical narrative and telling their teacher what they remembered about it. Rather, they were actively engaging in historical arguments. Arguments of both significance and purpose. Of course, understanding significance and purpose for many is a lifelong endeavor; but how much more equipped will these students be to ask such questions of their present after dissecting their meaning in the past?

Historical thinking not only builds up students analytical skills, it gives them a necessary tool belt to engage with life’s biggest questions. They can think historically about their own world and rather than simply be bystanders to the events of the day, they can enter into the conversation in order to offer up their own solutions, just as they offer their own interpretations of the past. Historical thinking matters.