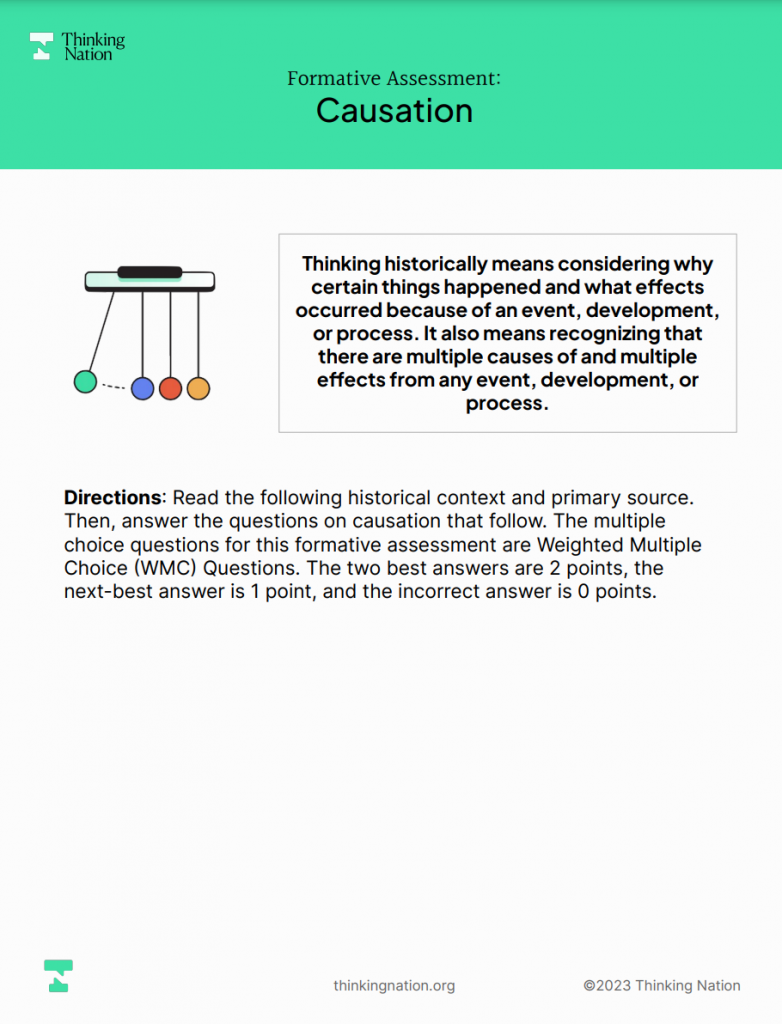

At Thinking Nation, we believe that teaching students how to think historically is key to cultivating thinking citizens. With this, though, we recognize that equipping teachers with the time and tools to do so is essential. This is why we make common assessments the backbone of our curriculum.

Common Assessments are simply tests or quizzes given by teachers across grade levels and/or departments. When multiple teachers give (almost) identical assessments, it dramatically increases opportunities for teachers to collaborate with one another to push student learning forward. While many subject areas prioritize giving common assessments, these are often lacking in social studies classrooms; and even if social studies departments do administer these, they are often based on content-knowledge rather than the skills that define thinking citizens. Our mission is to change that.

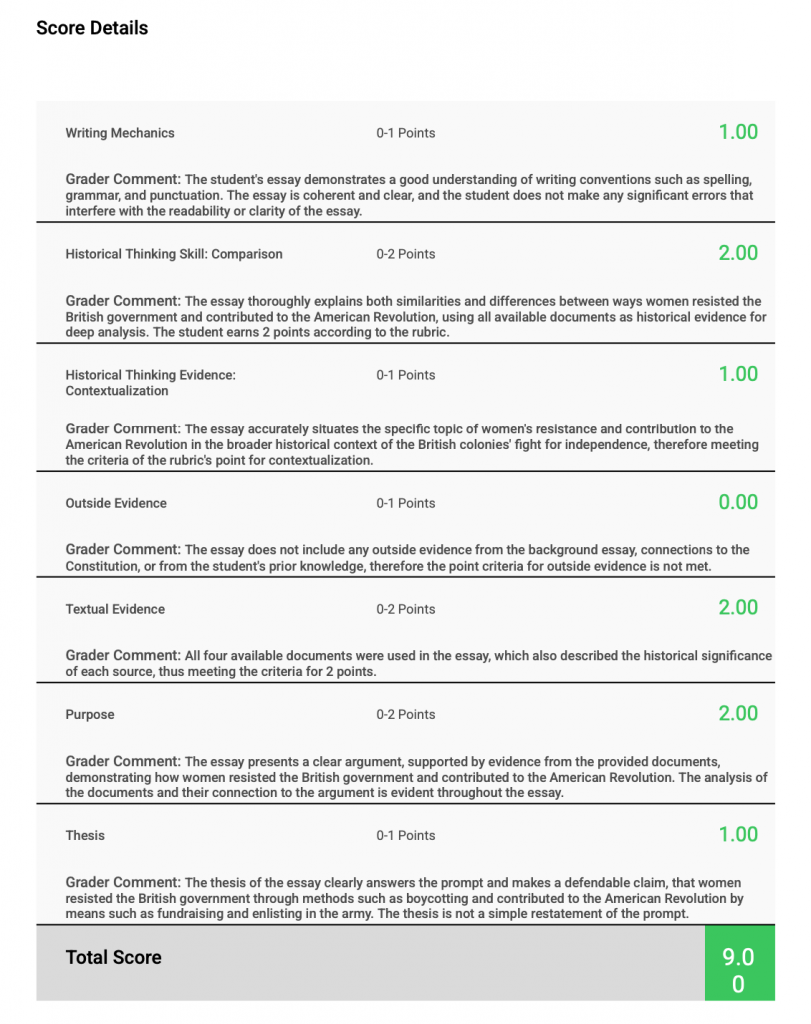

Thinking Nation’s formative assessments and DBQs assess how students think, not what they think. Our rubrics are designed to give students and teachers targeted feedback on the thinking process. When these are given as common assessments across multiple classrooms, student growth is not just localized within one classroom but is shared across a school or district. Teachers can have baselines for conversations, data analysis, and re-teaching lessons. When more teachers can talk about pathways to student growth, students benefit. And that is the goal of education.

Since our DBQs vary in topics but assess the same skills, this also means that the assessments can be common without being identical. This gives teachers freedom to use our materials for whatever content they are currently teaching in their class. Even if two classes are administering two different DBQs from our online platform, the resulting collaboration is just as helpful because the conversation is about students’ ability to think historically, not memorize historical information.

When we assess our students on their understandings of history, we can better serve their needs. We can meet them where they are at. With common assessments across a school or district, we can meet more students’ needs and elevate more students’ learning experiences. This allows student growth to go from isolated incidents to district-wide trends. It can transform the way that history departments work. For these reasons, Thinking Nation is committed to providing teachers, schools, and districts the curricular and professional development resources to realize these goals.