As expressed in previous blogs, at Thinking Nation we prioritize supporting teachers as they work to teach their students how to think historically. One way we do this is by offering to do guest lessons for teachers at our partner schools. This week, I had the opportunity to do a guest lesson on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program in an 11th grade classroom. The opportunity had me reflecting on just how important teaching the past through primary sources can be.

In this lesson, students work to write an essay answering the prompt: “Evaluate the extent to which FDR’s New Deal improved the lives of African Americans.” Since history is complex, we wanted students to wrestle with the complexity of this era of massive legislation and that legislation’s impact on a particular group of Americans. Some of the documents analyzed point out how much progress for all Americans (including Black Americans) came as a result of New Deal policies. Others show the implicit (and sometimes explicit) discrimination toward Black Americans that was a real problem with New Deal legislation.

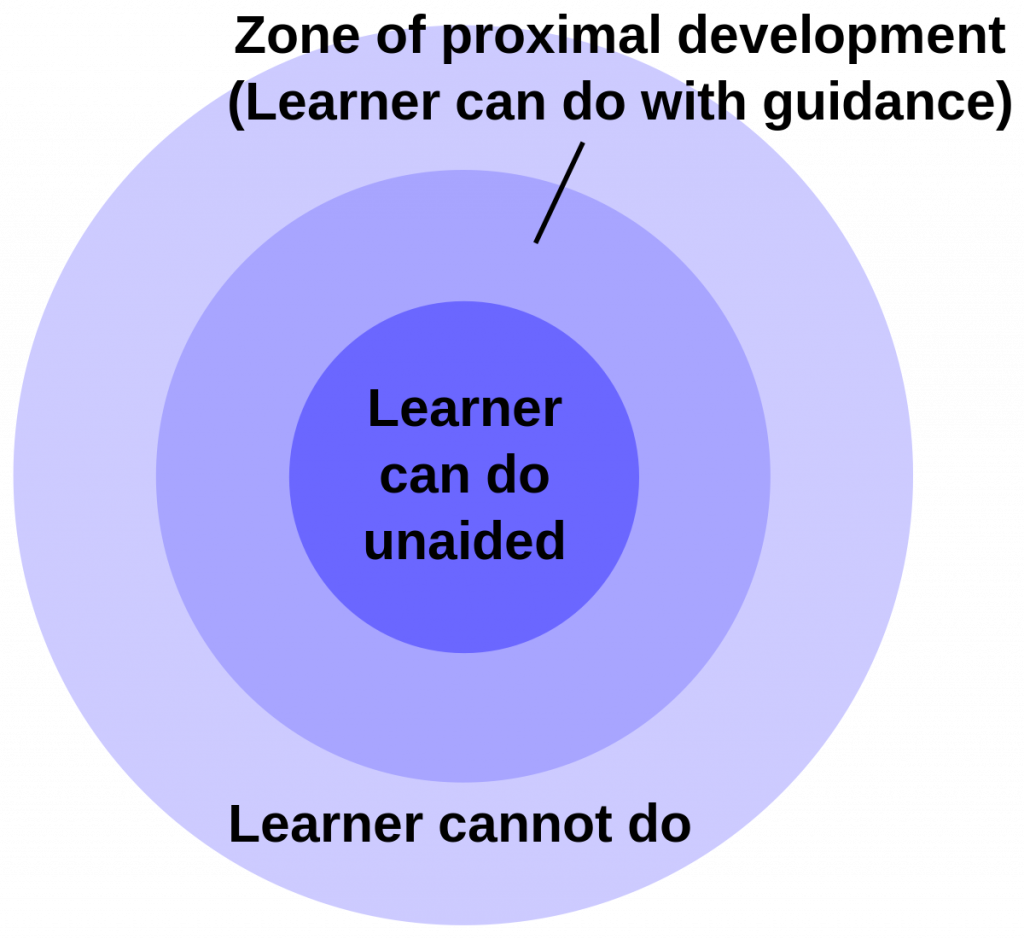

Rather than being mere passive receivers of a story regarding this era of American history, students were engaging with arguments about the past, modeling the very type of thinking historians employ in their own research.

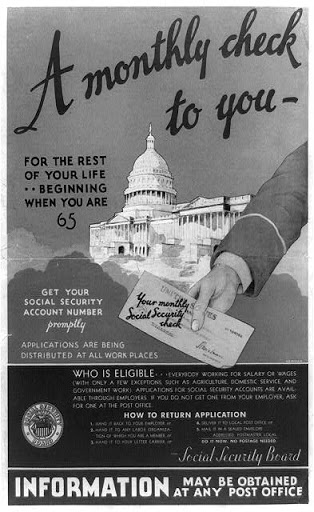

After reading a testimony from Charles Houston (a representative of the NAACP) to the House Ways and Means Committee, where he pointed out the systemic inequality that occurred in the Social Security Act, we looked at how this document fits within the prompt of improving the lives of African Americans. Houston pointed out that since Agriculture and Domestic Service were two industries dominated by Black Americans (and those industries were excluded from Social Security benefits), Black Americans received no support from the federal government’s program even though statistically they had the most to benefit from it.

The content of his testimony is mostly an example of how The New Deal did not improve the lives of African Americans. But one girl raised her hand. “Can’t this be seen as a positive example of Black progress?” she asked. Her classmates looked confused as if they were thinking “Oh no, she really isn’t paying attention.” She continued, “In this case, a Black man is testifying to Congress and they are listening. So even though he is pointing out negative aspects of the New Deal, the very fact that he is in that room shows progress toward more racial equality.” We were all impressed. In all honesty, I had not even seen that argument before.

In that instance, a student recognized the nuances of the past. She became an active participant in historical study. She was not just a learner of the past, but a doer of history. The complexities of the prompt at hand, and perhaps history more generally, came alive. Seeing that lightbulb shine was not just a powerful moment as an educator, it was an empowering moment for the student. She had an evidence-based perspective that shined light on history’s complexity. This is the type of (historical) thinking that we want. It’s the type of moment in the classroom that cultivates thinking citizens.