We recently published a short introductory video to express who we are at Thinking Nation and our hopes for the history classroom. Here it is!

Author: Zachary Cote

Historical Thinking Paves a Better Way Forward

This week, I came across a statement by the Big City District-University Social Studies Group. In it, the authors write that “social studies must have a prominent role in the ‘build back better’ Conversation.”

They (rightfully) contend that any conversation around equity or combatting learning loss must contain a plan for a robust social studies curriculum in classrooms. Of course, we joyously agreed with their statement and accompanying sentiments. If we want a better way forward, we need a social studies curriculum that is centered on historical thinking.

This week, I also attended an online forum on equity in education in Los Angeles. Throughout the forum, the speakers pointed out the gross physical inequities exacerbated by this past year of virtual learning. Whole families who only had internet through a couple of smart phones had to figure out how multiple children were going to “attend” school every day. In blunt terms, it was impossible.

Focusing on physical inequity is crucial to building a better way forward. We need to ensure that every child has the physical means to grow and learn. But this can’t be the end of the road toward equity. There is still a necessary conversation about what we do now that students have equal access. Do they still have an equal experience?

Unfortunately, the answer is still no for so many communities. Resource rich students are still ill-equipped to sustain the future of our democracy. This is why the above-mentioned statement is so true. In order to overcome the ailments of our society and democracy, we must rethink how students are introduced and taught to engage with the past. To deny the connections between the past and present is to deny reality. We have to teach students to critically engage with the past. We have to empower them to be doers of history, to think historically. When students are empowered to do the above, they can build a more equitable future. They can pave a better way forward.

As we move into the 2021-22 School year, may we re-evaluate how we are teaching social studies to our next generation of engaged citizens. Let’s center historical thinking as a way to empower our students. When our students are confident in their ability to think about the issues of the past, they will be able to intelligently engage with the issues at our present.

Thinking Nation is ready to partner with schools who see this tall order and know that it is time to act. We want to empower students to think historically. They can’t wait any longer.

Historical Thinking Combats Polarization

Why are we so polarized right now? If “the other side” says it, we automatically discount it. We don’t know how to debate, or even argue well. We just yell. We devour information that feeds our own perspective and spit out any information that we disagree with as “fake news.” We are hurting ourselves, hurting our local communities, and hurting our national democracy.

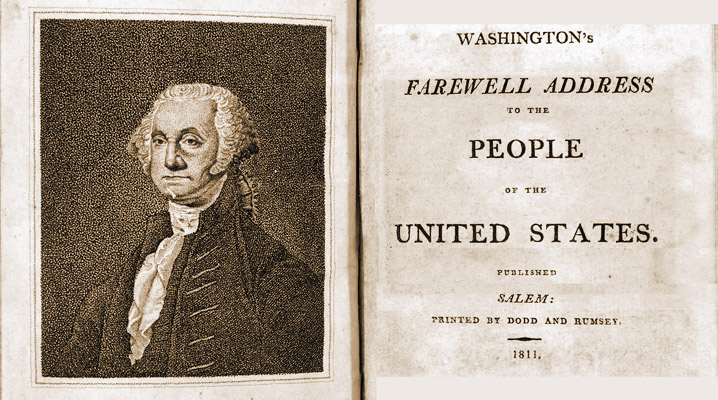

In his 1796 Farewell Address, our first President George Washington warned his country that the “spirit of party” “serves always to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration. It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection.” he continues, in words that will jolt the eyes of any modern reader. This spirit of party is “A fire not to be quenched, it demands a uniform vigilance to prevent its bursting into a flame, lest, instead of warming, it should consume.”

We have been consumed.

But we don’t have to remain this way. We can still put the fire out. But, like any fire, this is going to take time, a lot of resources, and the skill to do so properly. Within this solution is the core of our curriculum: historical thinking.

When we think historically, we are skilled to navigate evidence appropriately, engage with multiple perspectives, recognize causation, recognize trends, and have the knowledge of historical precedents needed to make informed decisions about our present. Historical thinking is critical thinking. It’s slow thinking, counterintuitive to the click bait culture our social media accounts reward. It’s persistent thinking, willing to engage with a topic enough to actually understand it. It’s empathetic thinking, willing to compassionately understand those we study rather than jump to ill-informed conclusions.

Historical thinking is the type of thinking we need the upcoming generations of citizens to embody if we don’t want to continue to be consumed by the fire of factions and polarization. Let’s slow things down, revolutionize the history classroom, and cultivate a Thinking Nation.

Independence Day, 245 Years Later

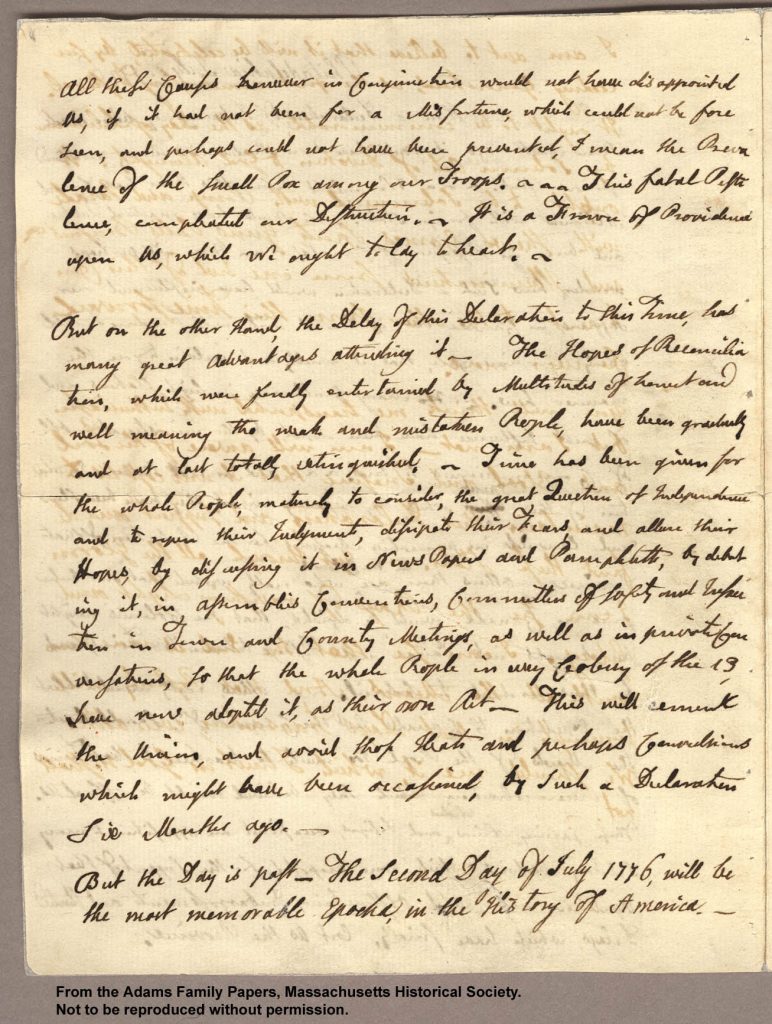

According to John Adams, we should all be firing up our grills and lighting off our fireworks today. 245 years ago, he wrote a compelling statement to his wife, Abigail Adams. Taking pen to paper on July 3, 1776, Adams reflected on the previous day’s accomplishment of the Continental Congress approving the Declaration of Independence:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

John Adams to Abigail Adams, July 3, 1776

While we may laugh at Adams’ certainty that the 2nd of July would be a day of celebration, his words were still prophetic. Every year, on July 4th (the day the Declaration’s final version was adopted) many Americans celebrate Independence Day. It’s a day to remember the eventual success of the American Revolution and the birth of the United States.

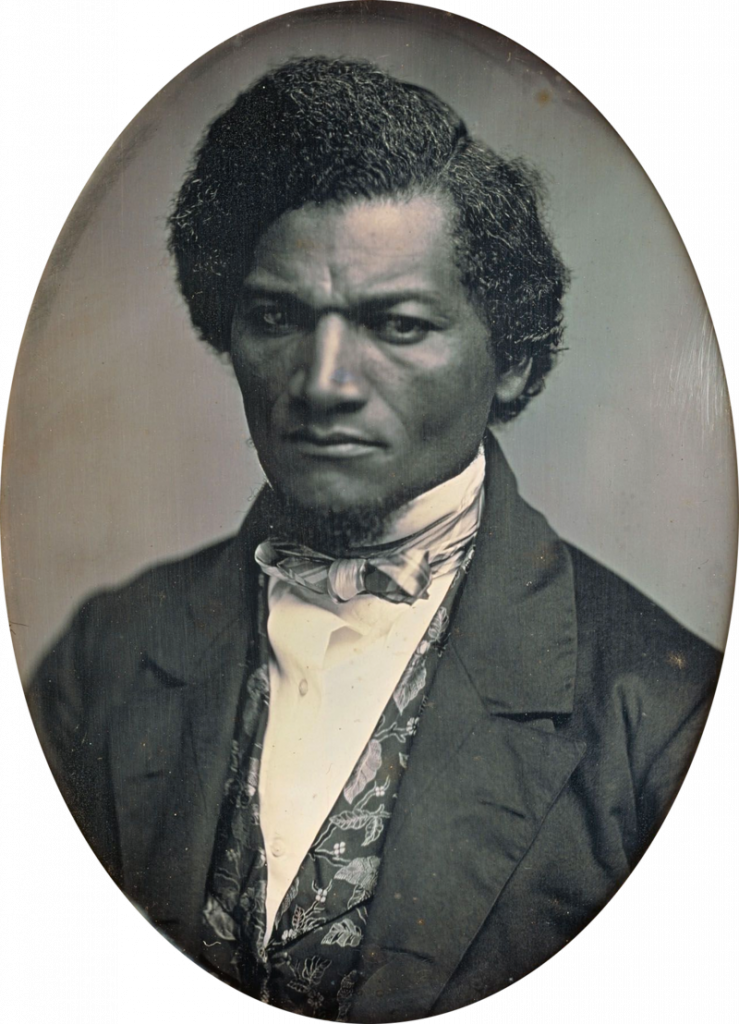

But, as we saw in the blog two weeks ago, not everyone took such pride in America’s independence day. Speaking on behalf of enslaved Americans in 1852, Frederick Douglass pointed out America’s hypocrisy in celebrating its own independence while it continued to strengthen human chattel slavery within its borders. Speaking to hundreds in Rochester, NY but knowing full well that his speech would be sold in pamphlet form across the country, he declared:

The freedom gained is yours; and you, therefore, may properly celebrate this anniversary. The 4th of July is the first great fact in your nation’s history — the very ring-bolt in the chain of your yet undeveloped destiny… This Fourth [of] July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.

“What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852.

Douglass made sure his audience recognized America’s double standard. He was able to praise what America’s founders did do while also condemning what they didn’t do. By doing this, he paved a path forward for us. Over a hundred years later, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. continued in this vein in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

“I Have a Dream,” Martin Luther King, Jr. August 28, 1963.

With these words, he revealed both the great feat of America’s independence and the principles it set forth as well as America’s inability to live up to those principles. Like Douglass, he held these two facts in tension.

Us modern readers must also be willing to hold these facts in tension. First, we cannot be arrogant enough to assume that the “bad check” is fully resolved in 2021. As any parent of a toddler will admit, making a mess takes far less time than cleaning it up. American slavery lasted 339 years. After that, Jim Crow segregation lasted 89 years until Brown v. Board (1954). It would be another decade before the Civil Rights Act was passed. Therefore, in 2021 we are only 57 years from the Civil Rights Act that MLK and others worked so hard to pass. To say that the work toward liberty and justice for all is finished is nothing other than willful ignorance.

Still, we’ve come a long way in realizing America’s promise as laid out in the Declaration. Based on this, as well as the words of the Declaration itself, we still have cause to celebrate! The Declaration affirms: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” These words are worth celebrating, not because we’ve fully lived up to them, but in order to remind us to continue to do the work in order to “form a more perfect union.”

As we celebrate our nation’s birthday this weekend, may we too hold these truths in tension. On one hand, we live in a country that is built on a glorious principle, that all are created equal. On the other hand, our history is a history of our country that has yet to fully live up to this principle. That, of course, does not make the principle any less worth celebrating. As Douglass declared in his speech, “Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.”

May Independence Day be both a day to celebrate the 245th birthday of the United States and a call to action to live out the Declaration’s principles “on all occasions,” and “whatever the cost.”

The Filibuster

The filibuster has been in the news a lot lately. With the increasing polarization in Congress, Democrats in the Senate have been advocating abolishing the filibuster since the end of 2020. With holdouts like Dem. Sen. Joe Manchin III who has said that he will not vote to end it, Democrats are unable to move forward with abolishing the filibuster, which would make it easier to get much of their progressive legislation passed.

But what is the filibuster? Simply put, it is a mechanism in the Senate that gives the minority party more control over a piece of legislation. Historically, to filibuster meant to actively speak on the Senate floor in order to delay the legislative process and prevent a vote from taking place. Now, senators do not need to stand on the floor. A senator can simply invoke the filibuster, and unless there are 60 votes to overrule the filibuster (this is called cloture), the bill is essentially stopped in its tracks. Democrats today argue that since Republicans are constantly filibustering their legislation, Congress has essentially become a minority rule legislature. Even though Democrats control the White House, House of Representatives, and (narrowly) the Senate, they cannot pass progressive legislation because of this. Of course, a democracy is by definition “majority rule,” so many argue that by keeping the filibuster in place, it is preventing democracy from happening. This begs the question: why did the filibuster begin in the first place?

Really, filibusters have existed since the beginning of our Constitution. In September 1789, Pennsylvania Senator William Maclay wrote that the “design of the Virginians… was to talk away the time, so that we could not get the bill passed.” Long, seemingly pointless speeches have been eating up legislation from the beginning. But it was not until 1917 that cloture was established. From then, if 2/3 of the Senate voted to, the debate (the filibuster) would end. Then a vote could take place. In 1975, that vote changed to only 60/100 Senators instead of 67. The trajectory of U.S. history, then, is to curb the stalling nature of filibuster in order to keep Congress doing its job: to legislate.

Today, as debate continues over what to do with the filibuster, this history should help. When the filibuster becomes more than just a tool of the minority party to force compromise, but rather becomes a tool to prevent “the other side” from winning, perhaps reform is needed.

Does this mean the filibuster should be abolished? Well, Democrats may not like the long term consequences of its abolition once they no longer control Congress. Then, Republicans, or some future party, could pass sweeping legislation in the same way they hope to now. Still, as our history reminds us, reform is often good and necessary. It’s why we have amendments, it’s why we have term limits for presidents, and it’s why we have a Supreme Court to interpret laws and how they may change over time. Now, it’s just Congress’s job to figure out what reform goes beyond just helping the particular political cause of the moment and actually strengthens the Constitutional system that has existed for more than two centuries.

Juneteenth: America’s Holiday

For the first time in almost 40 years, Congress established a new national holiday: Juneteenth. In such a politically polarized world, the quick bi-partisan support for this holiday should not go unnoticed. The Juneteenth National Independence Day Act passed unanimously in the Senate on Tuesday, June 15. It passed the House the next day, 415-14, and then yesterday June 17, it was signed into law by President Joe Biden. Something that passed so quickly and with such bipartisan support must be understood. After all, it is now our 11th federal holiday.

Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, when Union Army Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger announced in Galveston, TX that the 250,000 enslaved men, women, and children in the state were free. While they were technically free as early as January 1, 1863 when Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, because Texas never fell to U.S. troops during the Civil War, it took two and half more years for the news to reach them. Beginning that day, Black Texans would celebrate its anniversary every year after.

For over 150 years, Black Americans have celebrated this joyous holiday. For many years, to come, all Americans will celebrate it. Juneteenth is for all of us. Historian Eric Foner has called Reconstruction, the period after the Civil War, America’s second founding. The first 100 years of our nation’s history was defined by a great paradox: Celebrating liberty while spreading slavery. In order to begin the ongoing process (which we still must pursue, after all, even the founder’s acknowledged the task of forming “a more perfect union”) of living to our creeds, the nation had to abolish slavery. Juneteenth is a clear way to celebrate this second founding in the same way that we celebrate our first founding every July 4th.

There is also something incredibly significant about adopting a holiday to celebrate this second founding, not on some anniversary of a legislative act, but on a day that Black Americans have celebrated for a century and a half. By honoring a day that has such a rich cultural heritage, the government reminds us that federal holidays are for the people. Black Americans have set the tone for celebrations of this day over generations, it is now fitting for the rest of America to join the celebratory chorus.

On July 5th, 1852, Frederick Douglass reminded his Rochester, NY audience of America’s double standard in celebrating Independence Day every July 4th.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy — a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.

Frederick Douglass, 1852

Douglass rightfully condemned the hypocrisy of celebrating July 4th in a nation that enslaved millions. Now, we get to celebrate Juneteenth as the day our new republic began. Not perfect, but more perfect. Tomorrow is a big day. It deserves any respect we hold for the 4th of July. So let’s celebrate!

Historical Thinking Cultivates Citizens No Matter Their Time or Place

I recently listened to an episode of the podcast, The Last Archive. Hosted by Harvard historian and New Yorker columnist, Jill Lepore, The Last Archive’s current season looks at conspiracy theories and hoaxes in American history. “Who killed truth?” she often asks throughout each episode. In this episode, “Believe it,” she looks at the role of early radio in the 1930s and how it sowed doubt in the American public.

Unable to see what was being said or heard, early radio shows could take advantage of their audience’s gullible sensibilities. For instance, there was apparently mass hysteria when Orson Welles broadcasted his famous “War of the Worlds” in 1938. People around the country genuinely believed that there was an alien invasion. You could hear their fear in subsequent interviews. As Lepore summarized it, if it was on the radio, people believed it.

This of course sounds a lot like much of the “fake news” that can dominate the internet in the 21st century. Unequipped to validate sources, people will take a Facebook or Instagram post at face value, share it to their friends, and before you know it, a fake story has spread to millions of believers. Obviously this is extremely unhealthy for democracy and civic life. Like Americans almost 100 years ago were duped by the new extravagant technology of the radio, we are duped by wild stories on the internet.

Many people recognize this problem. Whole organizations are dedicated to equipping people to separate fact from fiction on the internet. At Thinking Nation, we applaud these efforts. But we also look to moments in the past like early radio to understand that these moments of doubt are not new. Targeted efforts to combat radio fake news were needed in the 1930s just like targeted efforts are needed today for the internet. But what if there was something broader and more holistic to combat these issues? There is! Historical thinking.

We place so much emphasis on historical thinking at Thinking Nation because we believe that these skills transcend time, place, and space. Using history to teach students to interpret documents, events, and their outcomes in the general can equip students to separate fact from fiction in the particular. Historical thinking allows our conversations to be richer, our evidence to be sound, and our arguments to be strong. Join us at Thinking Nation as we prioritize historical thinking in order to cultivate thinking citizens.

We’re Cultivating Historians, Not History Enthusiasts

A few weeks ago, our blog was entitled “Knowing History vs. Doing History.” In it, we briefly brought up the difference between a historian and a history enthusiast. History enthusiasts may know history, however, rarely do they “do history.” Today, we’ll take some more space to illuminate this distinction.

In the world of history, there tends to be two types of people interested in the past: historians and history enthusiasts. The former tend to explore the past in such a way to form arguments, riddled with nuance, exposing history’s complexity. Their study of the past does not stop at knowing what happened, but rather understanding what happened. This could take the shape of seeking out the causes of events, comparing eras or events, contextualizing a specific action within a larger setting, or even taking a broader approach and dissecting how things change or stay the same over time.

The interest of the history enthusiast is less complex. Fascinated by quirks of the past, the history enthusiast emphasizes unique ‘tidbits’ of information. This allows them to have an encyclopedic knowledge of whatever era or topic they are most interested in, but does not necessarily contribute to the complex vision that professional historians seek after.

Of course, the above examples of how historians explore the past embody the “4 C’s” that our curriculum is centered on: Causation, Comparison, Contextualization, and Change and Continuity over Time. When students interrogate the past through these historical thinking skills, the past becomes alive. Rather than being a stagnant pond full of facts, it becomes a roaring river with rocks and rapids to navigate. It becomes a journey of exploration, not merely a preordained pathway of knowledge.

So, as we reflect on this difference, may we ask: What type of history are we teaching in our classrooms? Are we relaying information about the past with simple, albeit witty, stories that may draw interest? Or are we equipping our students for the rapids of history, cultivating the necessary skills for them to construct knowledge and form arguments about the past? The former may be a helpful segue to grab attention, but it lacks depth. We must cultivate historical thinkers if we want to build up a thinking nation.

Resistance and Persistence for Equality: Honoring the AAPI Community

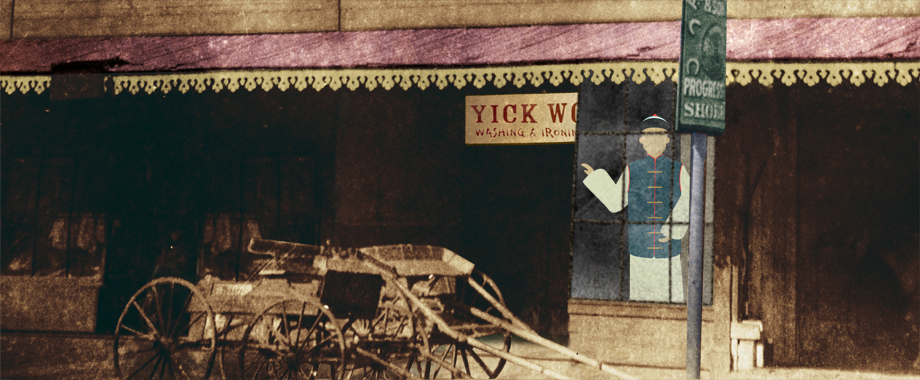

The month of May is Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month. As the month comes to a close, we want to take this week’s blog to honor those who resisted injustice and persisted toward equality within the AAPI community. This week’s blog will highlight three instances where Asian Americans called the United States to live up to its founding ideas of liberty and justice for all. Each of these stories come from our curriculum’s library of DBQs and we hope that as you engage with their heroism today, students will engage with their stories in the classroom.

Our first story of resistance and persistence comes from San Francisco in 1886. Chinese men Yick Wo and Wo Lee were denied permits to operate their laundry businesses under a new discriminatory law in San Francisco. While the law did not mention race at all, after the city council passed it, only white laundry business owners could obtain permits to legally operate in the city. Yick Wo and Wong Lee challenged this discrimination on the basis of the relatively new (passed in 1868) 14th Amendment, which states, “No State shall… deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” To put the amendment to the test, they continued to operate their businesses without permits, and then when threatened by the city, made their case in the U.S. legal system. Despite the new city law not explicitly referencing Chinese San Franciscans, Wo and Lee took their case (Yick Wo v. Hopkins) all the way to the Supreme Court to argue that the city’s laws violated their 14th amendment rights. The court unanimously sided with Wo and Lee and set a profound precedent in U.S. legal history. The court argued that just because a law is not racist on its face doesn’t mean it can’t violate a citizen’s 14th Amendment rights. Their resistance and persistence led to an important change in our justice system.

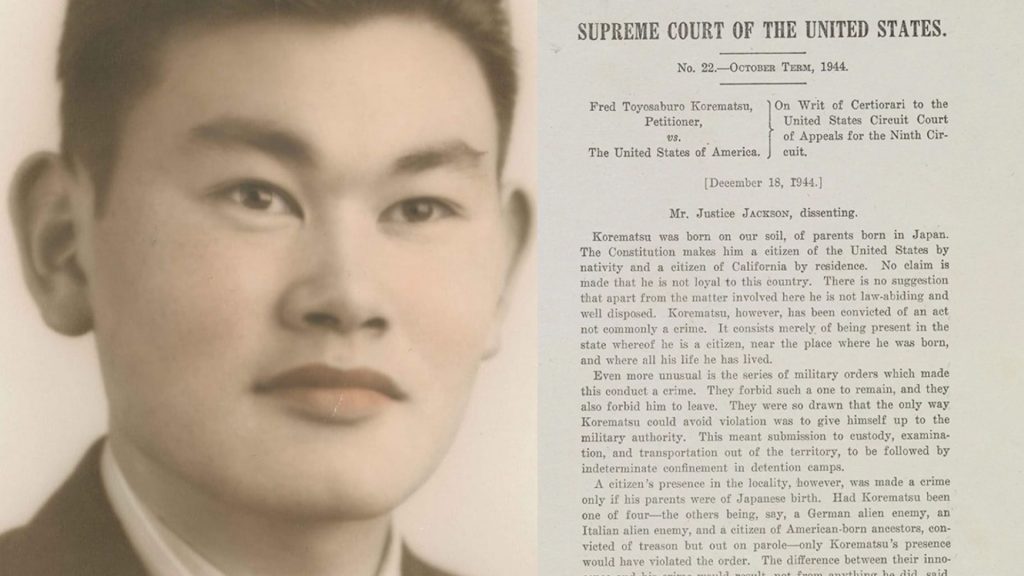

Our second story comes during the American tragedy of Japanese internment. During World War II, the American government forced Japanese Americans out of their homes, rounded them up, and forced them to live for almost three years in concentration camps in remote areas mostly in the Western United States. Resisting this unjust internment, Fred Korematsu hid in Oakland. He was later arrested and jailed for refusing to be taken from his home to one of these camps. The ACLU used his arrest as an opportunity to test the legality of Executive Order 9066, which President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed to intern Japanese Americans, arguing that it was in the interest of national security. Sadly, the U.S. Supreme Court did not uphold the 14th Amendment rights like it did in 1886 and ruled 6-3 in favor of Korematsu’s conviction. Still, Korematsu paved the way for America’s apology for this atrocious act against Japanese Americans. In 1982 a federal commission found that the Executive Order was shaped by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” In 1988, the government paid $20,000 in reparations to each surviving internee. Korematsu’s resistance set the foundation for justice.

Our third story takes place in 1965. Thousands of Filipino farmworkers in California were working underpaid and in inhumane conditions in California farms. Filipino-native Larry Itliong, who led the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) led a successful strike in Coachella to raise the wages and working conditions of Filipino farmworkers. From there, the workers followed the grape crops to Delano, CA. When refused the same wages they were granted in Coachella, they planned another strike. But to avoid Mexican workers taking the jobs once the Filipinos went on strike, Itliong approached Cesar Chavez, the leader of the association that primarily served Mexican farmworkers. Initially hesitant, Chavez agreed to help Itliong and join the strike. This became the great Delano Grape Strike that lasted 5 years and became an international movement to advocate farmworker rights. If it were not for the resistance and persistence of Larry Itliong, the movement would have never come about.

As May ends, may we remember the contributions of the above three men and so many more within the AAPI community who resisted injustice and persisted toward equality on behalf of Asian Americans throughout the United States.

History Does Not Have to be Familiar to be Relevant

When most people talk about history needing to be relevant for students, I fear what they mean is that it needs to be familiar. These voices argue that if a historical subject is too different from the students that learn it, they’ll just tune out. Or that students need to see themselves in the past in order for it to be meaningful in the present. While there are some truths to this, I fear that if we cling too tightly to this false equivalency, that familiarity = relevance, our students will miss out on just how great history is.

To be fair, the motives behind this false equivalency are good. Unfortunately, so many students are taught a specific narrative about the past that neglects the beautiful diversity of past characters. History is often taught from a purely political lens, leaving out the rich social, cultural, economic, and religious aspects. Or, even worse, history becomes a hagiography, where it is just a series of biographies of the past’s “great men.” These approaches to history miss so much richness, and it is true, can be very hard for students to be attracted to, especially if they can’t see themselves in those stories. We need a history curriculum that highlights diverse voices and perspectives and avoids simply conveying some grand narrative whose only grandeur is that it has been repeated over generations. Mere repetition does not make something more true.

Still, if we try to right this wrong by only focusing on whatever history is clearly connected to our present moment, we make history something that it never was supposed to be.

History is not meant to serve the agenda of the modern mind.* Just as historians rightly point out when politicians quote historical anecdotes just to show that they are “on the right side,” we must also challenge history curriculums that are all too directly tied to our current cultural moment. When we only focus on this history that is familiar or supports our current trends, we enable our own narcissism, believing that the past is just meant to serve our needs. It wasn’t.

As novelist L. P. Hartley opened one of his novels, “The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there.”

It is ok for the past to feel very foreign, or unfamiliar, when we study it. This lack of familiarity has the ability to humble us. It forces us to have empathy for those we study. It forces us to get out of our modern bubbles and seek to understand those not like us. It gives us the dispositions to navigate a world where people grew up differently from us, worship differently than us, adhere to political parties opposite of us, or uphold different customs from us. When we study an unfamiliar past, we better fit in with the human family. We see humanity in others before anything else. We have better ears for listening and better hearts for understanding. This has a much deeper relevance than simply making sure our students can see themselves in the past. It helps us become better people, ready to learn from those we’ve been told are so different from us.

At Thinking Nation, our goal is for students to engage with both the familiar and the foreign in the past. They can learn from stories they feel strong connections to, while at the same time seek to understand stories where the connection isn’t clear. Through this, they can be better citizens in both the U.S. and the world.

*Here, it is important to acknowledge that there is nothing wrong with our modern mind influencing our focus for our own study of history. Often, our own political, social, or cultural goals influence what parts of the past we want to uncover. Still, we must avoid trying to make the past fit into our present conceptions. There often will not be any subject that is a perfect fit for what we are looking for and we need to be able to wrestle with that complexity without simplifying past stories to fit our own outlooks.

Knowing History vs. Doing History

In last week’s blog, we emphasized the importance of depth over breadth. In recognizing the fact that we can never “cover it all,” teaching the depth of history over covering as much content as we can actually gives freedom to teachers. Not stressed about how much they need to cover, teachers can dive deep into particular historical subjects with their students in an effort to equip students to think historically. This brings us to today’s blog topic: Knowing History vs. Doing History.

First off, as we wrote about in our first ever blog, history is not merely “the past,” but the study of the past. With this in mind, “knowing history” does not simply mean knowing a lot about the past. Still, for the sake of today’s blog, that’s exactly how I want us to see it. Often, when people hear others spout off knowledge about the past, they respond with, “You know a lot of history!” This misrepresentation of history exists everywhere, from classrooms to movies. The fact is, while historians do in fact know a lot of history, this is not what makes them a historian. We must differentiate between the history enthusiast (those who love to collect tidbits about the past in a knowledge closet) and a historian. Historians do not merely know history, they do history.

This idea, of “doing history,” is at the heart of our curriculum at Thinking Nation. We don’t simply want students to passively receive historical facts (or a particular historical narrative) from their teachers. We want students to actively engage with the past, interrogating it in order to make meaning of the world that came before them. This is historical thinking. This is doing history.

Knowing history can puff up people as walking encyclopedias, quick to tout their knowledge superiority, but this does not produce the empathy and humility that results from being able to think historically. When we can “do history,” we can wrestle with competing accounts and narratives, we can investigate past stories, and we can learn to understand those that are foreign to us (even if not foreign in space, historical actors are foreign in time). This is not only more fulfilling than knowledge acquisition (we aren’t giving students fish, we are teaching them to fish), it is a humbling endeavor.

Furthermore, doing history not only makes us better historians, it also strengthens our critical thinking skills for all subjects. When students are equipped to think historically (to do history), they are better prepared to investigate robust math equations, analyze complex literature, and solve present scientific issues. The ability to merely cite various historical events does not have such interdisciplinary applications.

This is why we must prioritize depth over breadth. We must prioritize doing history over knowing history. When we do this, we empower students to actively engage with the past, and in turn, cultivate thinking citizens.

Depth > Breadth

“You can never cover it all.”

If there was a slogan that we history teachers should put on the front of every yearly plan, unit plan, or lesson plan, it should be this. In an education environment where history teachers are guided by chronological standards, it is no wonder that we often feel discouraged toward the end of the school year, lamenting what we have to cut out for the lack of time. I’ve heard “We just couldn’t get to it this year” countless times from colleagues. Unfortunately, the content-coverage approach to teaching history makes us feel rushed and dissatisfied with our results each year. It doesn’t have to be this way.

At Thinking Nation, we prioritize teaching historical thinking over content. We recognize that it will always be impossible to cover every important part of the past. This also means that it is impossible to make sure that every voice is heard or every story is told, even if that story is incredibly important to us or some of our students. But that doesn’t mean that our history classrooms cannot be incredibly impactful.

If we teach students how to think historically, they can apply those skills to historical topics that they are most interested in. Like in university-level history classes, students can engage in research projects where they apply the thinking skills that have been cultivated in their history classrooms in order to pursue historical knowledge on a topic of their choosing. Not only does this allow the content to feel more relevant to themselves, but it also pushes them to be actively engaged with the study of the past, not merely passive receivers of historical information. This is empowering.

If we focus less on the breadth of what we cover in class and more on the depth in which topics are engaged with, students can experience the power of doing history. They can be equipped to tackle any topic they feel pulled toward both in and outside of the classroom. No matter the subject in school, the major in college, or the career path they choose, when students are empowered to think historically they can apply those skills to be the leaders and agents of change we hope for them to be. That is far more important than knowing “at least I addressed such and such topic.” So, let’s prioritize depth over breadth when teaching the past in an effort to equip and empower our students for what lies ahead.

And if there was a second slogan, perhaps it should be:

“You will never get it perfect.”

And that’s ok.

The Discipline of History is Our Best Chance at Interdisciplinary Collaboration

One of the core aspects of our platform is providing schools with useful data on student writing performance, aligned to common core standards. Many curriculums also do this; however, they do not clearly and unabashedly align the content of their curriculum to the study of the past and the unique skills that that entails. We prioritize history and historical thinking while also providing schools with necessary data in order to drive student learning forward and provide schools helpful tools to ensure their students are equipped to do well on high stakes state exams. We can do this because the discipline of history is better set up than any other subject for interdisciplinary collaboration.

In our first blog of 2021, I brought up how I would show my students that everything is history. No matter what you are studying, it is history, because everything that is studied happened before this very moment. The different areas of emphasis among historians solidifies this fact. We have historians of science, medicine, religion, math, literature, art, economics, politics, the environment, transportation, and the list could go on… endlessly. History is the study of the past, and depending on one’s framework, that study can take a variety of forms. Due to this, the history classroom is uniquely set up at the level of secondary education to collaborate with any other discipline. It is versatile in its content, allowing for the adaptation of its accompanying skills to any particular field of study. History does not need to fit into a framework like the hard sciences or social sciences. Yet, unfortunately, history is often merely an afterthought in many school curriculums today. It rarely receives the notoriety of STEM or English Language Arts, and because of that, it also receives little funding. This is a travesty for both education and our democracy. It is why creating a “thinking nation,” to us, means emphasizing history education. It is why we want to create a teaching revolution that prioritizes the discipline of history as a core subject.

If we stop seeing history as its own silo of learning, we can expand that teaching revolution beyond history classrooms. If the other subjects taught at schools see history as the perfect partnering subject, no matter the content, not only will students better understand the context of any content area, they will be stronger thinkers and writers, applying the analytical skills fundamental to history to all of their subjects. The result? Empowered students and citizens, ready and equipped to make our future better.

When we see history as the bridge that connects all content areas, we can create more robust and rigorous educational atmospheres. Interdisciplinary collaboration is a powerful tool for teachers to provide the education our students need. We hope that by centering history and writing as the foundation of our curriculum and platform, we can come along schools to provide them the tools needed to equip students and cultivate citizens.

The Power of Resistance: Harriet Jacobs’ Story

This week, we’re going to veer a little from our normal coverage of teaching and doing history and look at a particular story from the past. This past week, I’ve been working on a new DBQ for our Ethnic Studies curriculum, which will be available to partnering schools next school year. For research, I read Harriet Jacob’s famous slave narrative, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which she wrote as “Linda Brent” knowing the potential repercussions of using her real name given her own personal story.

Harriet Jacobs’ story is so important for us to understand the lives of the enslaved in 19th century America. Even though I’ve read around her book for years, it was humbling to finally dive into the whole thing. At one point in her autobiography, she writes, “Slavery is terrible for men; but it is far more terrible for women. Superadded to the burden common to all, they have wrongs, and sufferings, and mortifications peculiarly their own.” Her narrative demonstrates just how hard her life was as an enslaved woman.

When she turned 15, her enslaver, Dr. James Norcom (in the book she calls him Dr. Flint) began to sexually harass her and “began to whisper foul words in my ear.” He even built a cottage on nearby land for Jacobs to live on so that he could have his way with her without drawing attention to his wife or the local town. Jacobs, determined to not let this happen, had sexual relations with a local white man and became pregnant. For her, “It seems less degrading to give one’s self, then to submit to compulsion.” When her enslaver told her to move to the cottage, she retorted, “I will never go there. In a few months I shall be a mother.” Norcom “stood and looked at me in dumb amazement, and left the house without a word.”

In a rather unique, but no less empowering way, Jacobs resisted her enslavement and her enslaver. In a culture where enslavers became rich off of human chattel from their own lust, raping their female slaves, Jacobs resisted. While she did struggle with her own moral conscience given her choice, she was determined not to let her enslaver’s greed and lust control her life and the lives of her children (she ended up having two children with the abovementioned man).

Jacobs’ story only grows in intensity. She ends up having to hide in her grandmother’s attic for 7 years, hearing and seeing her son and daughter, but unable to speak with them. After those 7 years, she was able to make her escape thanks to a local free black man’s keen awareness. She goes up to New York and is reunited with her daughter in Brooklyn, and then later, her son. Jacob’s story is one of victory. Although her trials were unspeakable, she persisted. She lived a long life in freedom with both of her children, an outcome that never existed for millions who were in bondage on American soil.

Jacob’s story is powerful and emotional and we are humbled to share her story as a part of one of our DBQs on American history.

Our Goals: To Empower, Promote Equity, and Cultivate Citizens

If you have been on our website’s homepage recently, you may have noticed a change. Now, when you head to thinkingnation.org, you see this slogan:

As we talked about last month, we are seeking a teaching revolution. One where the history classroom is more than just learning about the past, but learning how to understand the past. In short, one where historical thinking is prized. Today, we are going to look at some of the profound benefits of being able to think historically.

First, historical thinking empowers. As a principle, education should empower students. Yes, knowledge is power, but perhaps wisdom is the type of power we should all seek. While knowledge is critical, wisdom is the ability to discern what to do with that knowledge. The ability to think historically, to reason with the past, helps us to exercise that wisdom. It empowers us. When students learn about the past, no matter how inspiring the story, if they can’t think historically about the past, they are more like an encyclopedia than a true student. But when students contextualize the past, identify patterns and change, causes, and can make historical comparisons, they are empowered to actively engage with the past and not merely be passive receivers of a particular narrative. That empowerment builds confidence with how they engage with their present. A particular narrative no longer needs to be simply accepted, but it can be interrogated and wrestled with. Historical thinking empowers them to do so.

Historical thinking promotes equity. There is a clear gap in our educational world. Students who have historically had access to a variety of resources consistently do better than students who haven’t. Numerous schools and organizations have dedicated their time and energy to closing this gap, but we still have a lot to do. One thing we can focus on is equipping students to think historically. While knowing about a diverse past is critical to helping students see themselves in others, we must also equip students to reason with the past. We must work hard to push our students to think critically about the documents and people of the past. We must work to equip our students to analyze historical perspectives. We must work to help our students articulate their analysis in clear, evidence-based writing. When students feel like they can draw their own conclusions about the past because they have been taught to think historically, they are better able to engage in dialogue about robust topics, even if those they dialogue with know more than them. As the adage goes, we must teach students how to think and not what to think. If historically-disadvantaged students are empowered with the above skills, we will have a more equitable education system.

Lastly, historical thinking cultivates citizens. At the core of who we are at Thinking Nation is our desire to cultivate thinking citizens. We want students to be equipped with the skills to participate in a robust democracy. Part of these skills is the ability to think historically. While we live in “the information age” we also live in an era of disinformation. In order to sustain democracy, students need to be able to sift through a variety of sources and perspectives, make analytical judgments, and draw evidence-based conclusions. The study of the past is an excellent way to cultivate these skills. When students engage with history, they have to ask deep and difficult questions about the nature of people and their decisions. These skills, embedded in the ability to think historically, allow students to be informed citizens, ready to tackle the issues of the present in order to preserve democracy.

The ability to think historically is central to our curriculum. We believe that historical thinking empowers, promotes equity, and cultivates citizens. Join us as we use the study of the past to build a more democratic future.

Our Professional Development Empowers and Equips Teachers

Today is our 30th blog! In the last 30 posts, we’ve defined key ideas like history, historical thinking, and its examples. We’ve explored the relevancy of the U.S. Constitution to our current moment, we’ve explored the richness of the historical discipline and its historiography, and tried to understand the present by looking to the past. At Thinking Nation, we want to equip all stakeholders in history education for their various roles. At the heart of our mission is to cultivate thinking citizens in our students through our historical-thinking centered curriculum. But just as important, we want to equip our teachers to be agents of change in a teaching revolution. This is why we prioritize professional development for all of our partners.

Practically, we want to make sure teachers understand our DBQ process, our scaffolded lessons, and our online platform. But good teaching isn’t just understanding the mechanics. It’s being inspired to walk into class every day, knowing that we teach the most important subject for sustaining our democracy and civic society. We are not merely conveyers of knowledge. We are empowering students to be the best they can be by teaching them to think critically and better understand where we are by understanding where we’ve been. As the ancient Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero put it, “to be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child.” By teaching history and historical thinking, we are cultivating mature citizens.

With this ethos driving our mission, our professional developments seek to reinvigorate history educators in their own missions. Like a conference does for so many of us, PDs should provide us a renewed sense of purpose in our vocation. This is why our PDs focus on both the philosophical and the practical. Once we are reminded of just how important history education is, we can understand the mechanics in our mode of teaching. It’s not until a person understands the beauty of a car that working on it has meaning. The same goes for teaching!

As we seek to cultivate thinking citizens, empowered by their ability to think historically, we want to equip teachers with both the understandings and dispositions to be successful in doing so. When schools join us in this mission, we ensure that educators feel inspired, supported, and equipped, starting with the professional developments we provide.

Our Online Platform Prioritizes Academic Excellence

Teaching in the last year has shown us just how important it is for lessons to be adapted for a digital platform. Teachers had to rethink lessons that were built for in person learning in new ways so that they could be administered digitally. Unfortunately, this approach can often come at the price of de-emphasizing the rigor of the assignment in an effort to ensure there is understanding of the “essential content” that needs to be acquired. But what if the rigor, the analysis, the deep thinking was the essential content?

With our online platform for administering DBQs (Document-Based Questions) and formative assessments for historical thinking and writing, we want to ensure that deep thinking and analysis are prioritized no matter if learning is taking place virtually or in a classroom. We want to provide teachers and students in all learning circumstances with the tools necessary to cultivate thinking citizens. Whether a teacher assigns our DBQs directly on our platform for students to complete, or prints out the PDF versions of our DBQs for students in class, learners have access to complex historical topics where they can employ historical thinking skills to better understand our past and be better equipped to engage with our present.

For a simple tutorial of our teacher and student platforms, head to our website and watch our videos on how to navigate the platform. We hope to come alongside teachers and schools who are pursuing academic excellence for their students and equip them with tools to do so. Our online platform for teaching, learning, and assessing historical thinking and writing gives teachers the flexibility they need in that pursuit.

Why Data Matters

Honestly, the idea of “data-driven instruction” bugged me for years. I hated reducing students to percentage points of growth. I hated “mining data” to refine my instruction. It all felt formulaic for something that was really an art in my mind. But my frustrations were based on misunderstandings. My premises were wrong. Data-driven instruction is truly key to providing the best education possible for our students, if we use this tool in the way it was intended for.

I often think in my head that the difference between a ‘good cook’ and a chef is the recipe. Anyone can make something delicious once, but to be an expert, the dish must be able to be replicated day in and day out in a restaurant or even in the hands of someone else if they are provided the recipe and some helpful tools. It would benefit us to think of teaching in this way. A good lesson or unit is worth praising, but expertise lies in our ability to build off that success to create more success for both ourselves and our students. Data affords us that opportunity.

At Thinking Nation, as we addressed last week, we provide grading services to our partnering schools. One of the strengths of this approach, summarized last week, is the ability to use data to enable vertical alignment across grade levels. We suggested that “having access to uniform data assessing the same standards over [the] years is crucial for the development of deep thinking and analysis.” If one teacher can build upon the gains of another teacher in cultivating historical thinkers and writers, we begin to look like chefs whose dishes are replicated in kitchens everywhere. We build a community of experts, not simply star teachers in isolated cases.

But we don’t need to wait for vertical alignment to be a possibility for data to be incredibly useful to our teaching. When teachers receive a data report (see a sample here), they get simple but helpful feedback on whole class trends and individual students. Using this data, teachers can go back to our document analysis worksheets to re-teach primary source analysis or review how to write a thesis statement and then check progress by implementing one of our formative assessments. Of course, teachers can go beyond Thinking Nation resources too, re-teaching or pushing rigor further depending on student needs. The important thing is that by having distilled data on student performance, teachers can best address their students’ needs in order to cultivate them as thinking citizens.

Data, especially in history and the humanities, can sometimes feel like a “4 letter word” (I know, I know, it is…). But in reality, when we have data on how students are doing on complex writing tasks like DBQs, we can tailor instruction specifically to meet their needs. Data allows us to see our students as people with specific skill sets and then take those observations and build something appropriate for their growth. With our online platform, teachers don’t need to spend extra time compiling that data; rather, they can dive right into it, reflect on it, and then do what teachers do best: teach.

Why Having Outside Graders Can Help Your Teaching

As part of our DBQ-based curriculum, we wanted to provide grading services for partnering schools. We believe that part of cultivating thinking citizens through the teaching of historical thinking is providing teachers with the tools and time to do so. But giving teachers back valuable time with our grading services is not the only reason having outside graders is helpful. Today’s blog is more on the practical side of our blogs, but it is just as significant for realizing our mission of cultivating thinking citizens.

First: time. As a department head, I noticed that one of the biggest obstacles for getting students to complete robust tasks that required deep thinking, analysis, and writing, was the grading that resulted for the teacher. On average, for every DBQ I administered to my 130-150 students, I spent 12+ hours of my weekends grading. I wanted to ensure that my students received their grades with feedback in a timely manner so that the topic and skills were still fresh on their minds and so I could do any reteaching that appeared necessary based on the results. Getting this amount of time from all teachers, on top of their many other responsibilities, was difficult. Teachers have hundreds of daily responsibilities, and many of those have to wait till after the school day. So giving that time spent grading back to teachers while still allowing them to implement rigorous assessments was huge for creating more buy in.

Second: Data and Vertical Alignment. Cultivating thinking citizens is a marathon, not a sprint. To truly equip students, teachers must partner with teachers across grade levels. When this vertical collaboration happens, teachers can best meet the needs of students throughout their academic careers. Having access to uniform data assessing the same standards over those years is crucial for the development of deep thinking and analysis. When schools use our platform and grading services, they can do just that.

Third: Bias. Of course, the issue of teacher bias when grading can be contentious. But there is plenty of research out there that reminds us that teacher bias when grading most often impacts students in minority populations (Just do an internet search of “teacher bias when grading” for dozens of research-based articles on this topic). But getting even more granular, all of us teachers have said “well they tried,” or “but they didn’t do the prework!” when we grade. Our grades for those individual students, then, reflect more than just the essay they’ve produced. Whether this is fair or not (we can save that debate for another time), it does not accurately reflect the student’s skills on that given task. This only hurts the vertical alignment previously mentioned and clouds the specific scaffolds that may be needed to further student growth. Teacher bias is inevitable, but when grading is done from an outsider to the classroom, unable to know the details of a particular student, then only the assessment at hand is being graded, nothing more. This removal of bias in the grading process ensures clarity and accuracy in the grading process, allowing for student needs to be met and for growth to occur.

We want to cultivate thinking citizens. Due to time constraints, the need for data and vertical alignment, and the potential for teacher bias when grading, having outside graders assess student work on a uniform rubric can truly elevate student work and empower them to be deep, historical thinkers. For this reason, at Thinking Nation, we have expert teacher-graders to provide clear and helpful feedback for both teachers and students on student writing.

History Teachers are Literacy Teachers, Too

Last week, we focused our blog on the need for a revolution in teaching history. Content-knowledge can no longer be the end goal of a history education. Content is merely the means to an end of creating historical thinkers. To be a historical thinker, though, literacy is key.

Often, when school administrators or instructional coaches remind their history departments that “they teach literacy too,” it almost sounds as if the history teacher is only providing a supporting role for the more important English- Language Arts teacher and curriculum. After all, at least in California, it is the ELA standards that are assessed by high-stakes state exams. But this assumption profoundly misunderstands the power of a history education, centered on historical thinking, in cultivating both thinking and literate citizens.

In fact, many of the Common Core standards in literacy may in fact be best suited for the history classroom. When we look to the news, social media, or the political landscape, these common core skills (citing textual evidence, identifying a central idea, defending a claim, etc.) are rooted in history. When people look for the present moment to be contextualized or understood more clearly, they often look to historians to make relevant judgments. In fact, in the world around us these skills of literacy are almost always rooted in the study of the past.

With this landscape in mind, part of the needed teaching revolution is for history teachers to reclaim their role as primarily teachers of literacy. We want students to be able to interrogate documents, identify key evidence, and make defensible claims with that evidence. Yes, when many in education hear these goals, their minds quickly go to the English classroom and the Common-Core standards privileged in those classrooms. But the history classroom has so much to offer here. Not merely as a support role, but as leaders in equipping students in literacy.

For this reason, Thinking Nation’s rubrics are clearly aligned to Common Core standards. For students to be successful on our DBQs, they must be able to craft claims, cite evidence, identify central ideas, and write in a professional style. When we teachers require this type of writing and analysis of our students, we reclaim our role as teachers of literacy. We bring about opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration, demonstrating to students just how transferable the skills they gain in the history classroom are to their entire education.