Happy Teacher Appreciation Week!

At Thinking Nation, we are so fortunate to work with such dedicated educators, committed to empowering their students with the skills and dispositions necessary for success. I’m continuously reminded of their hard work when I come to a campus, lead a PD, or hear great stories of teachers from our Implementation Specialist, Will Pulgarin. Today, in honor of Teacher Appreciation Week, I want to share two stories from one of our partner schools in California that really exemplify the paradigm shift we strive for as an organization.

When I arrived to Cabrillo Middle School in Ventura, CA for the first time, it dawned on me that the majority of the social studies department were multiple subject credentialed teachers, who taught social studies among other subjects like science, Spanish, or English. I was definitely excited to introduce the world of historical thinking to this group, but also, admittedly a little hesitant to the receptiveness of teachers with little or no history background.

But wow, if growth mindset was embodied in a team, I think I found it! Of course, I shouldn’t have been surprised by this, as Carly Donick, former California Council for Social Studies and National Council for Social Studies Middle School Teacher of the Year is their department leader (I was fortunate enough to present alongside Carly at this year’s CCSS conference).

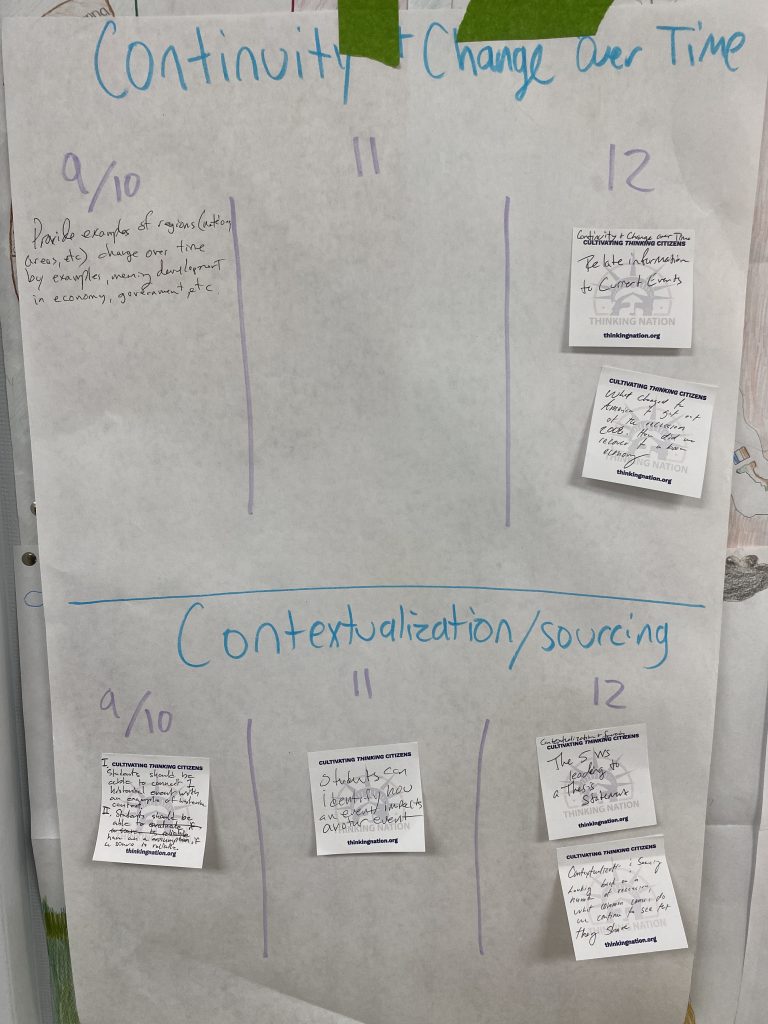

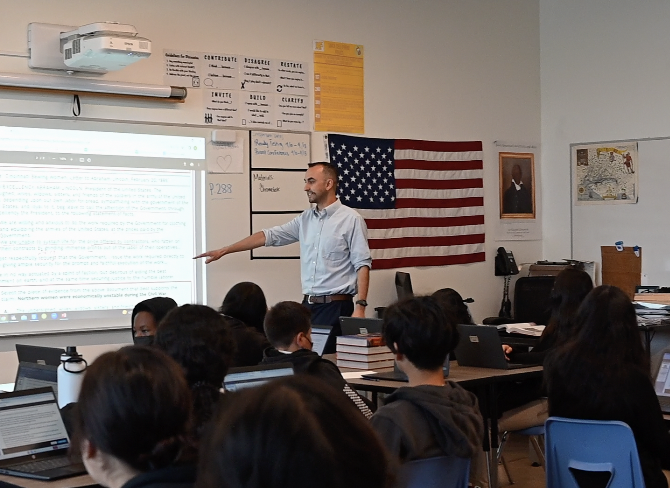

While I have been so impressed with their whole team this year, I was able to be in two of their classrooms this year, both 6th grade ancient civilizations. In the fall, when I was in Mrs. Klopfenstein’s class, we analyzed how the development of writing in ancient Mesopotamia changed over time. We analyzed a secondary source table, compiled in the 1800s, that showed how cuneiform changed over time, used our THINKs protocol, and discussed what continuities and changes we noticed. I was blown away at the responses from her students. They were thoughtful, analytical, and curious. When given the chance to think historically, they rose to the occasion.

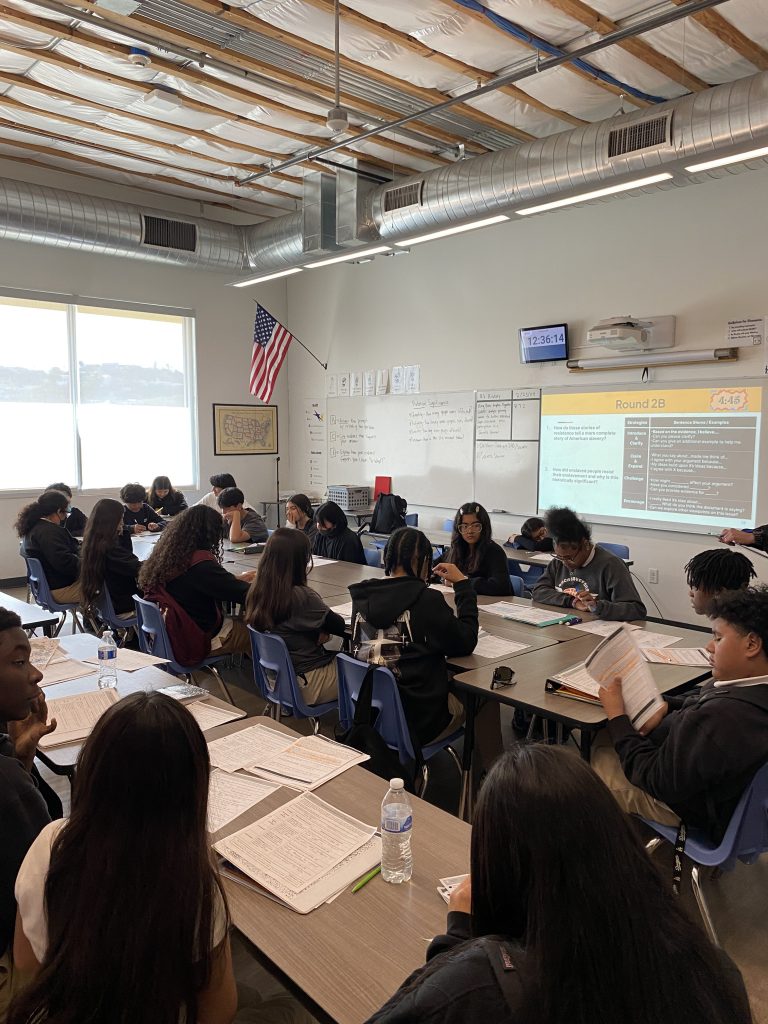

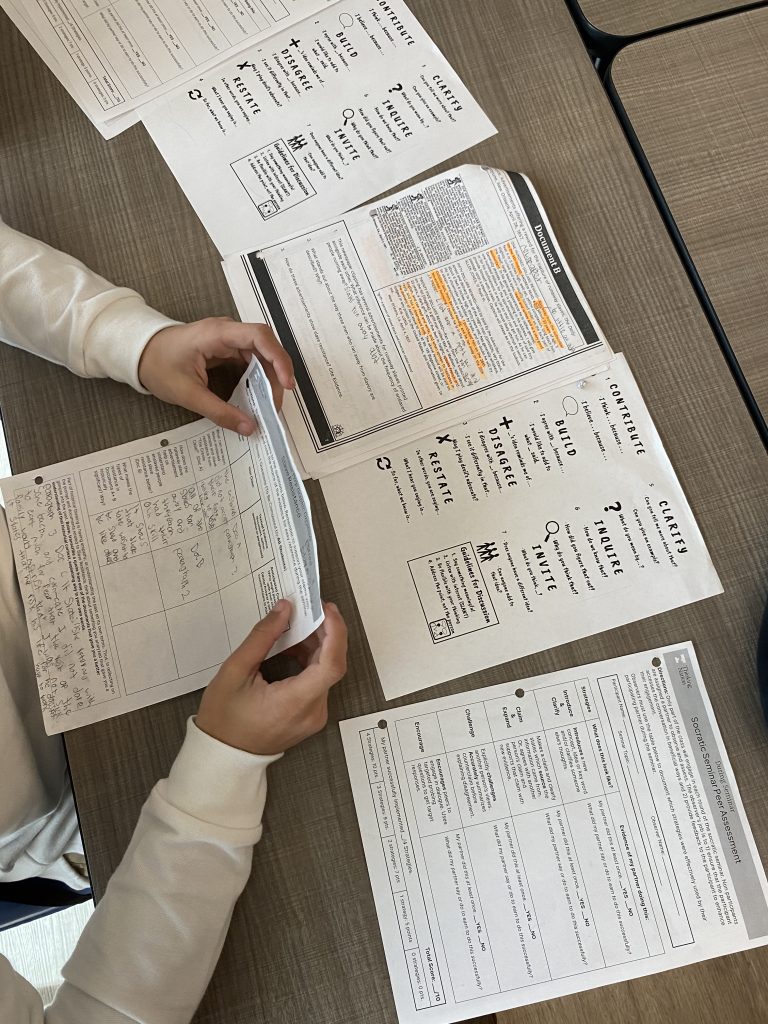

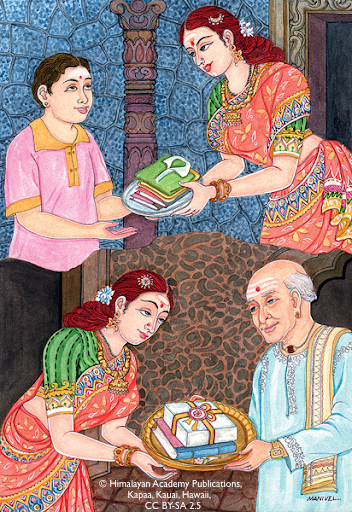

In second semester, I had the chance to help facilitate a socratic seminar in Mrs. Brady’s classroom. The students were using primary sources from Confucius and Laozi to compare the philosophies of Confucianism and Daoism. Honestly, I wasn’t sure what what going to come of this, as these two philosophies aren’t usually at the top of potential conversations to have among 6th graders. Still, as the students sat in a fishbowl seating arrangement, with the inner circle discussing questions like “What is the role of structure and order in a government influenced by Confucianism?” and “How would you summarize a good government based on the Daodejing?” I was so impressed by their discussion.

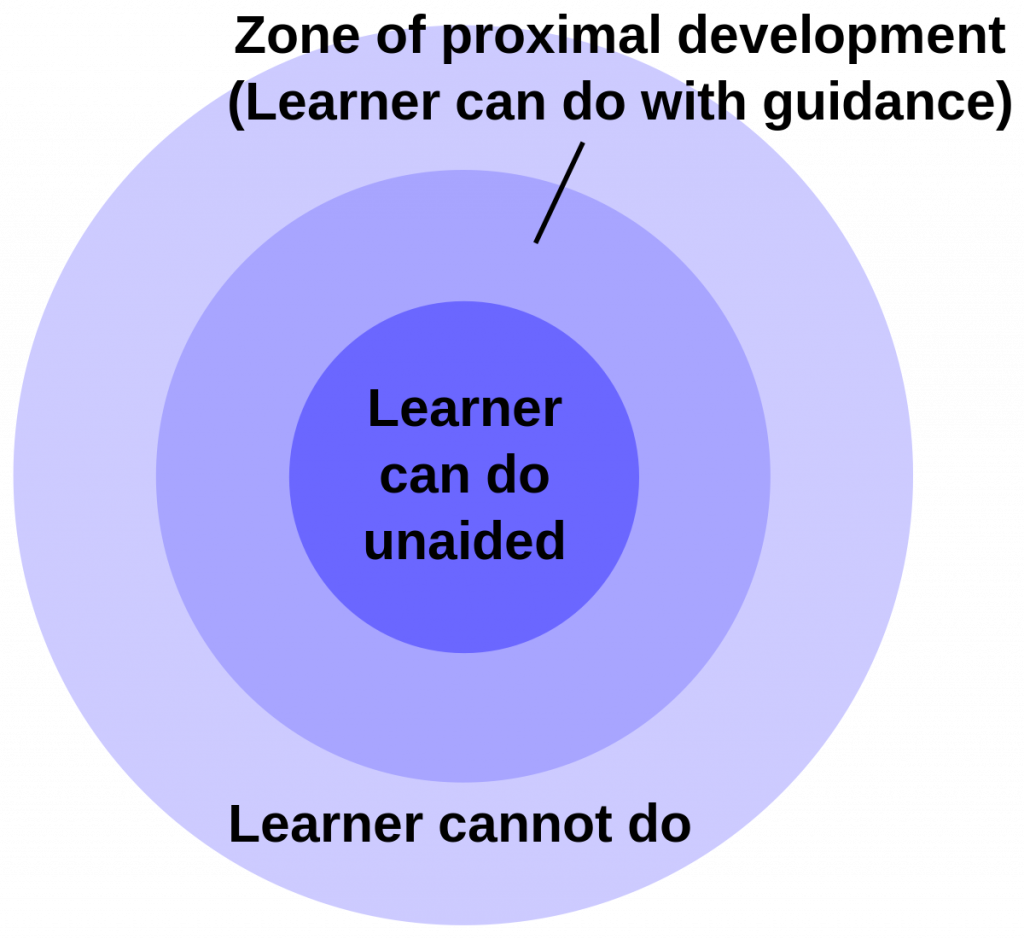

What especially impressed me, though, was their ability to work together in discussion, rather than at odds with one another in a debate. When the students got to the question, “According to the Daodejing, why should a ruler use ‘non-action’?” the class became silent. One of the students looked at me and said “We don’t know how to answer this.” Another student chimed in, “Yeah, Daoism was a lot harder to understand than Confucianism.” In response, I just said, “Ok, then try just talking about what you do understand from the text, don’t worry about the question.” A brave student began one of the most exciting sequences of discussion I’ve witnessed. Students began to just discuss the Daodejing and as they did, they began to weave in the idea of non-action.

After a minute or two, the whole group began adding their suggested interpretations to the question! What seemed out of reach for individual students became conquerable when the learning became communal. This demonstrated the pedagogical power of a Socratic Seminar. I left that class period so impressed by the culture of intellectual grit that Mrs. Brady had cultivated.

Stories like the ones above are happening all over the country in Thinking Nation classrooms. Recently, teachers have shared similar stories with me Arkansas, Indiana, Illinois, Washington, D.C., Washington, and New York. Each of these conversations is incredible rewarding.

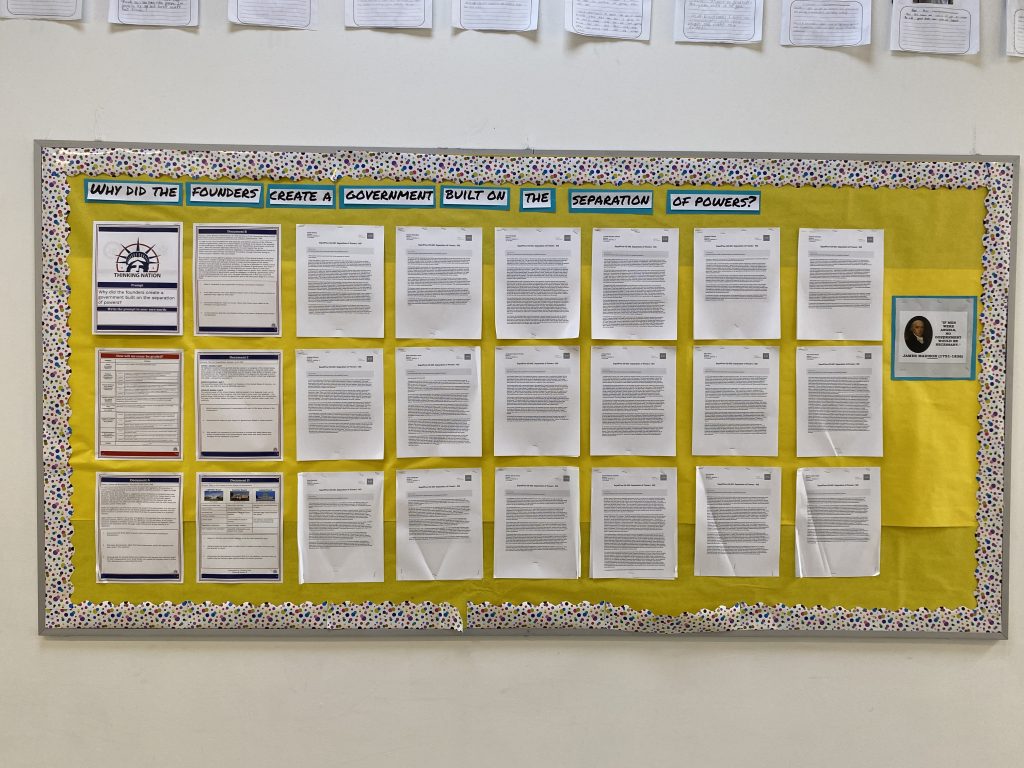

Thinking Nation’s vision is that every student is empowered with the skills and dispositions necessary to contribute to a flourishing democracy and thrive in an ever-changing world. What sometimes can feel like a moment, is turning into a movement.

If you’re still reading, and you want to consider what this could look like in your classroom, school, or district, reach out! We’d love to chat.

Happy Teacher Appreciation Week!