For those of you who have followed along with the last couple of blogs, you’ve seen that we’ve changed and added things over summer (more to come!). Today, we want to explain what is really at the core of these exciting shifts: our new brand identity!

If you go to our website right now, you will see that we have a new logo and colors to define who we are. We are really excited about our new brand identity and especially excited to explain why! (If you’re a partner school who has already had beginning of the year PD with us, this is probably just a review!).

First, why change? As Thinking Nation has grown into more schools across the United States, we’ve also had so many more conversations with people from different contexts. Throughout these conversations, we’ve learned a couple things about how people see us.

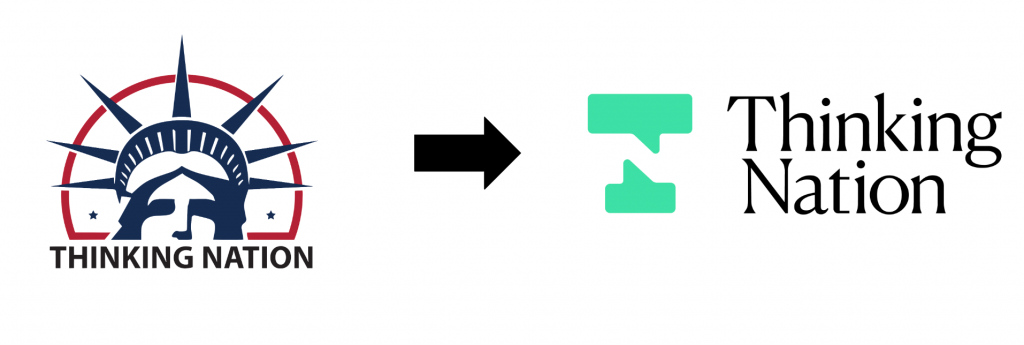

First, people assumed that we only covered Civics and American History. With the red, white, and blue, and Lady Liberty as our identity, who could blame them? However, like calling our essays “DBQs” took an extra layer of explanation, we’d have to take extra time to explain that we focus on social studies more broadly and that we really want to emphasize the disciplinary thinking that is inherent to good study in our field.

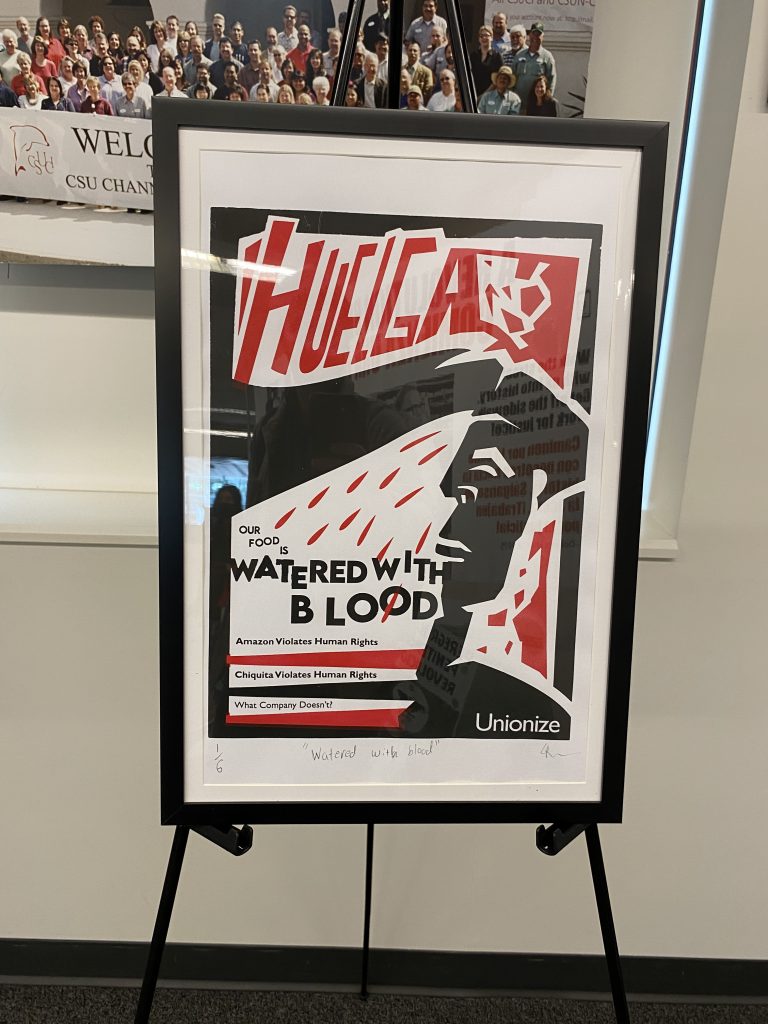

Second, many people saw our organization as partisan. However, a crucial aspect of our nonprofit mission is to be nonpartisan. We believe that good history and social studies education transcends political ideologies and can encompass both sides of the aisle, even if our current culture wars think otherwise. By focusing on the “why” of our discipline as the chief aim (rather than the “what”) we are proud to work with schools in a variety of political contexts. After all, the two largest states we work in are California and Texas. Historical thinking is for everyone, even if we disagree come election day.

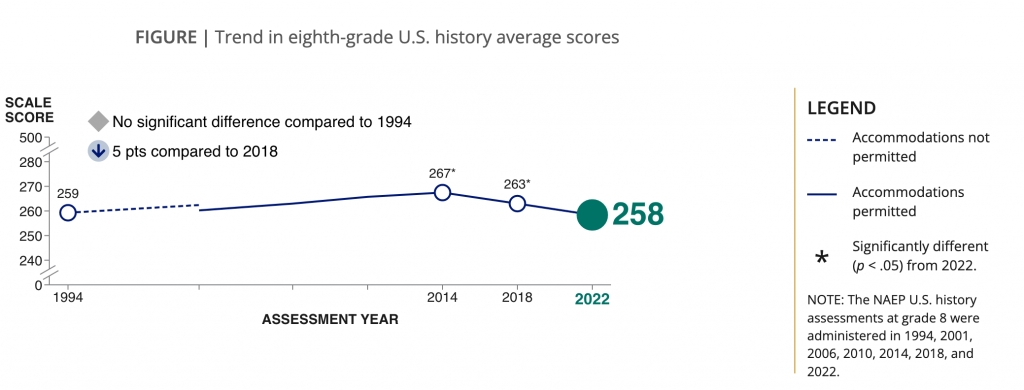

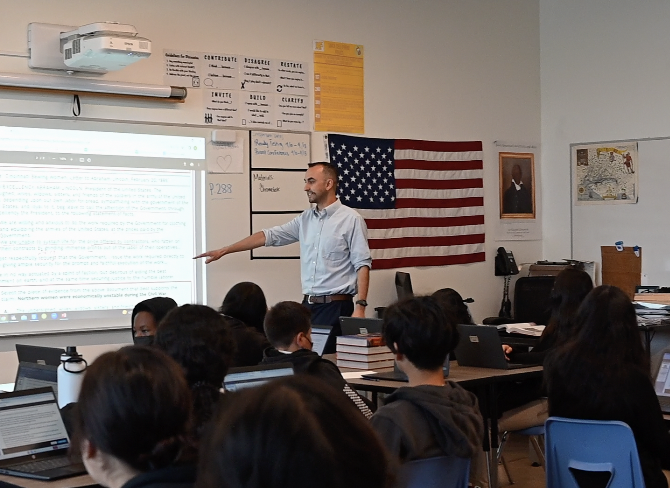

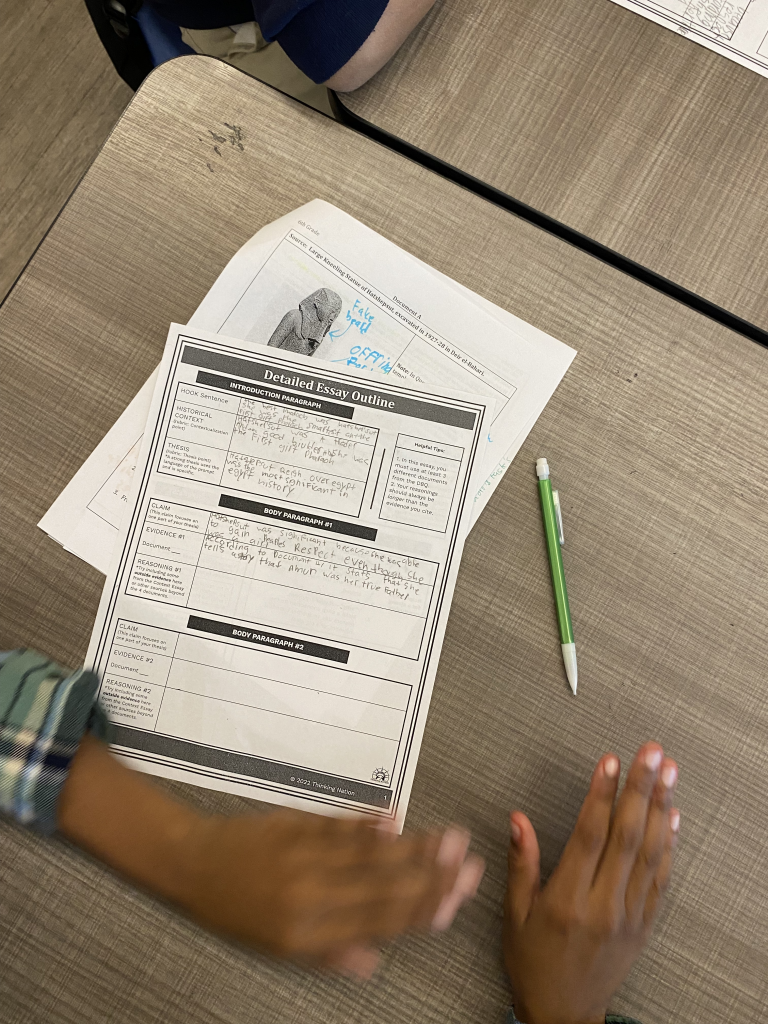

As expressed on our website, we want to shift the paradigm of history education. This is our purpose. We believe that when students learn how to think historically, they are better equipped as citizens. They can lean into the tension produced by listening to multiple perspectives. They can take the time to contextualize the stories they come across. They can empathize with others in an attempt to understand rather than judge. If we can shift the way we see social studies away from a memory-based education and into a thinking-focused education, our students are better served. We wanted a brand to represent this.

Our new brand, designed for us by Lunour, gets to this vision. With two dialogue bubbles, we stress the importance of nuance. There is never only one historical narrative, but history is filled with multiple perspectives. Dialogue bubbles illustrate that. Similarly, when our students engage in disciplinary study, they have to recognize that what they study is not stagnant. Scholars are in constant dialogue about the subjects they study. In fact, historiography, this study of historical writing, demonstrate that the discipline of history is one big dialogue about the past.

Not only do dialogue bubbles get to the heart of how we should teach and learn in social studies, they also get to the heart of our vision: “that all students will mature into thinking citizens, equipped with the essential skills to participate in a robust democracy.” If we want to sustain a pluralistic society governed through democracy, we have to learn to talk with one another. Through our work, we hope to equip educators to empower students for that future, a future where empathetic conversation dominates the public square, not bitter polarization. We’re excited for a logo that captures all of this!

Oh, and it’s pretty cool (in case you haven’t noticed yet) that the two dialogue bubbles make a “T” and the negative space makes an “N.” A Thinking Nation is built on dialogue.

To wrap up this lengthy post, we want to acknowledge some logistics. Thinking Nation is a small nonprofit, so this new brand identity will come out in waves. We will update our website, platform, and social media first. We are currently working on updating our curricular resources to fit the new brand, but this will take some time! So, if you see some materials in our old brand and some in our new, know that we are working hard at bringing everything over to our new and exciting brand! Our mission hasn’t changed, but we’re excited for an identity that better reflects who we are as an organization.

Happy beginning of the school year!